When Carli Leon heard the news of a child who died in February during the current measles outbreak in West Texas—the first child to die of measles in the U.S. since 2003—her initial reaction was “That could have been my kid.”

Leon, a 42-year-old mother of two in Cleveland, Ohio, had always intended to vaccinate her children. But then, while pregnant with her first child in 2012, a family she nannied for suggested she read a book that claimed to describe the dangers of vaccines. “It just snowballed from there,” Leon recalls. As a soon-to-be first-time mom, Leon says, she was lonely, and the idea that vaccines could injure her kids scared her. She was quickly welcomed into the antivaccine community, where she found a sense of belonging. She began fearing the risks of vaccines more than the risks of diseases she had never seen—precisely because vaccination had made them so rare.

“I wasn’t stupid,” she says. “I was just getting brainwashed.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Fears about vaccines have been around since the first one was developed against smallpox in the late 1700s, but vaccine hesitancy has risen in recent years. Now ongoing measles outbreaks reveal the growing threat it poses to public health. Researchers are learning what contributes to vaccine concerns and how people can effectively address them.

Why Is Vaccine Hesitancy on the Rise?

Many factors that are now driving vaccine hesitancy have been around for centuries, such as uneasiness with injecting a foreign substance into a healthy body and the impossible expectations for vaccines to be “100 percent safe,” says Alison Buttenheim, a professor of nursing and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. “What’s different now,” she says, “is the double whammy of the politicization of the pandemic and COVID vaccine and now the new [federal] administration.”

Before COVID, vaccine hesitancy mostly clustered in certain groups, but the pandemic’s barrage of misinformation amplified questions and doubts about vaccines. “A lot of people had no clue how toxic the [vaccine misinformation] environment was,” says Heidi Larson, who studies vaccine hesitancy at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “People who were taking vaccines for granted got exposed [to misinformation], and now there’s no turning back.”

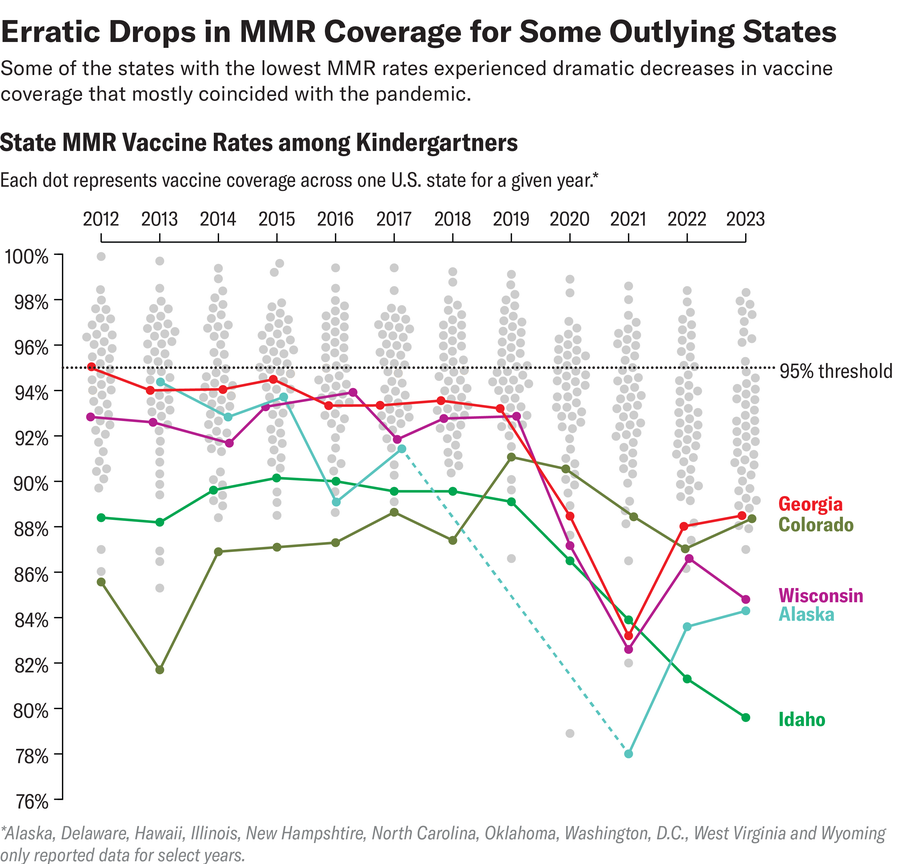

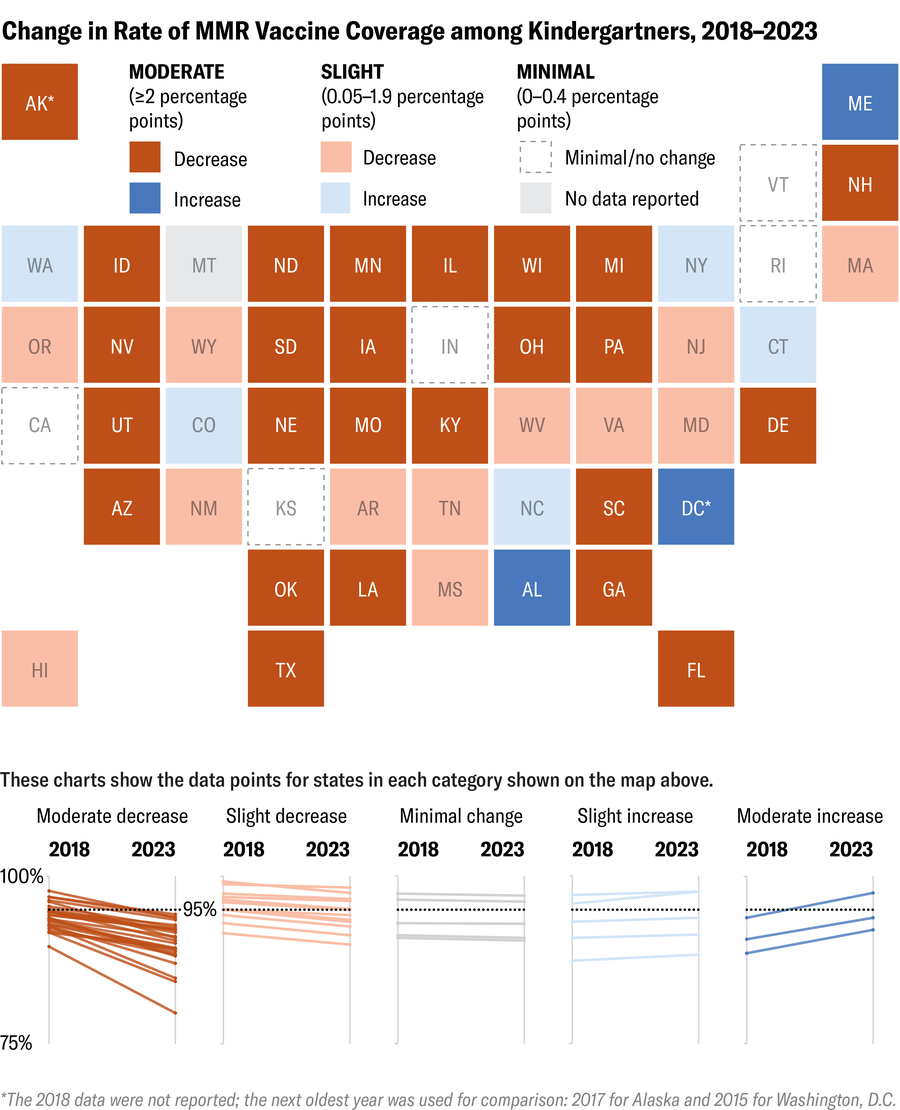

Missed wellness appointments for children during the pandemic contributed to the recent national dip in childhood immunizations, but another factor was the spillover from COVID vaccine concerns. Multiplestudies have documented the effect of COVID vaccine hesitancy on childhood immunization rates, including a reduced willingness among parents to vaccinate against measles.

“Certainly we’re seeing more hesitancy across the board,” says Nathan Boonstra, a pediatrician at Blank Children’s Hospital in Des Moines, Iowa, and chair of the state’s immunization coalition. Historically vaccination has had bipartisan support, and Boonstra has been frustrated as it has become increasingly politically polarized. “I’m worried that identity will strengthen, and we’re going to see more hesitancy from people who align politically in a certain direction.”

The problem is not confined to the U.S. A 2023 UNICEF report found childhood vaccine confidence declined during the pandemic in 52 out of 55 countries studied, and other countries are seeing similar political polarization around vaccines.

“The biggest driver of the decline [globally] was 18- to 34-year-olds, an age cohort that felt they had to compromise their lives the most for something that wasn’t affecting them as badly,” Larson says. But that age group is also most likely to make vaccination decisions for their children in the coming years.

The current spread of measles—with more than 700 cases across 24 states—is an alarming reminder of the high stakes around falling vaccination rates, says Paul Offit, an infectious diseases physician and director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The outbreak happened because a critical percentage of parents are choosing not to vaccinate their children because they’re scared of vaccines,” Offit says. He adds that a large part of that fear is a result of the decades-long advocacy against vaccines from Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., the new secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In the weeks since taking the helm of the HHS, Kennedy has made several moves to stymie vaccine confidence, including canceling the Food and Drug Administration’s advisory committee meeting to determine next year’s flu vaccine, suggesting he will replace key vaccine advisors and postponing the next Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory committee meeting on vaccines. Recently, the National Institutes of Health—an agency overseen by the HHS—announced it will terminate dozens of grants for vaccine hesitancy research. “[Kennedy] believes there is a poison being given to children in this country that is causing chronic disease, and that poison is vaccines,” Offit says. “It doesn’t matter how many studies are done to show he’s wrong.”

In response to inquiries sent to Kennedy, HHS spokesperson Emily Hilliard said, “We can confirm the NIH is adjusting its funding priorities to better serve the American people, which includes a reduction in funding for vaccine hesitancy research.” Hilliard also directed Scientific American to Kennedy’s Fox News opinion piece about the current measles outbreak, where he notes the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine’s effectiveness in prevention but also promotes vitamin A as a treatment. (Several children in West Texas are now receiving treatment for vitamin A toxicity.)

Shortly after publishing the op-ed, Kennedy made false or unsupported statements about measles and the measles vaccine during a Fox Nation interview. Offit also drew attention to Kennedy repeatedly stating that “the decision to vaccinate is a personal one,” even though a population needs high, uniform levels of immunity—as high as 95 percent—to prevent the spread of measles because it’s very contagious.

After a second child with measles died this month, Kennedy wrote on social media, “The most effective way to prevent the spread of measles is the MMR vaccine.”

How to Effectively Discuss Vaccine Safety

In the response to Scientific American, the HHS’s Hilliard highlighted “ongoing research into the safety and efficacy of vaccines” as a priority. Daniel Salmon, a vaccine safety researcher at Johns Hopkins University, is waiting to see how that pans out. Vaccine safety research has historically “been underfunded, slow and not very responsive to public concerns,” he says. “I’ve long argued for the need for more ongoing vaccine safety science resources, but it’s got to be good science—robust, objective, rigorous.” Salmon, however, is nervous about how Kennedy might define high-quality vaccine safety science. In March federal officials announced the CDC—which is under the HHS—will conduct a study on vaccines and autism. Reportedly this investigation will be led by a widely discredited researcher who has published antivaccine papers and was disciplined for practicing medicine without a license.

Salmon says that subtle changes in how people talk about vaccine safety can help rebuild trust. For instance, he suggests stating that “vaccines are very safe” instead of broadly saying that “vaccines are safe.” This can prevent mistrust when someone learns about extremely rare but possible adverse effects of vaccines. “Then explain that adverse reactions are either mild and transient or very rare,” Salmon says. “People can handle the truth.”

Leon recalls two pivotal moments that eventually led her to vaccinate her daughters. The first was seeing her antivaccine friends misinterpret study findings on vaccines for pertussis, or whooping cough—helping her to truly understand “cherry-picking” of results or statements in papers to support already held beliefs. The second moment was after her cesarean delivery, when a friend asked her, “Why don’t you trust the science behind vaccines, but you trust the science of surgeons who perform that procedure?”

Her friend “just kept asking me very valid, logical questions,” Leon says. “There was no animosity.”

That approach is similar to motivational interviewing, a technique that University of Colorado vaccine hesitancy researcher Sean O’Leary says can be very effective. “The basic concept is having a conversation in such a way that a person makes a health behavior change because they now understand why that change fits with their own internal motivations,” he says.

O’Leary also emphasizes the importance of reminding people that “the vast majority of parents are vaccinating their kids according to the recommended schedule,” he says. “Refusing vaccines is still an outlier behavior.” A small amount of outlying behavior still endangers the larger community, however, which is why experts agree that a key strategy in building vaccine confidence is to mobilize and engage those who do vaccinate, reinforcing those social norms.

“It’s really more about just having good conversations, becoming a trusted messenger.” —Sean O’Leary, vaccine hesitancy researcher, University of Colorado

Buttenheim suggests people pay attention to state legislative bills about vaccines, get to know their state legislators and “learn how to have productive conversations about difficult topics with people you love.” But, she adds, have realistic expectations. “Beliefs and identity are tightly interwoven, so changing beliefs may require a painful—or impossible—shift in identity,” she says.

When engaging in or observing conversations online, Boonstra encourages people to do so “in good faith.” “You want them to see that you’re presenting a good, logical, compassionate argument for vaccines,” he says. “It’s never going to happen in the moment. You might change their thinking over time.”

It took several months of conversations with her friend before Leon came around. What changed her mind wasn’t being bombarded with links from online arguments or “people telling [me] I was abusing my child”—an accusation that made her dig in her heels. O’Leary also advises avoiding arguments, which only “put people off. It’s really more about just having good conversations, becoming a trusted messenger,” he says.

Voices for Vaccines, a parent-led organization that works to increase vaccine confidence, has tool kits for talking about vaccines and courses on becoming a trusted messenger. Salmon recommends the online tool Let’s Talk Shots for vaccine information based on people’s specific concerns.

Not everyone may change their mind about vaccines, but some, like Leon, eventually do so with time. “What works is people asking questions and being relatively patient,” Leon says. “I’m very thankful for people who helped me and stuck with me.”