November 13, 2024

4 min read

The U.S. Must Lead the Global Fight against Superbugs

Antimicrobial resistance could claim 39 million lives by 2050, yet the pipeline for new antibiotics is drying up. U.S. policy makers can help fix it

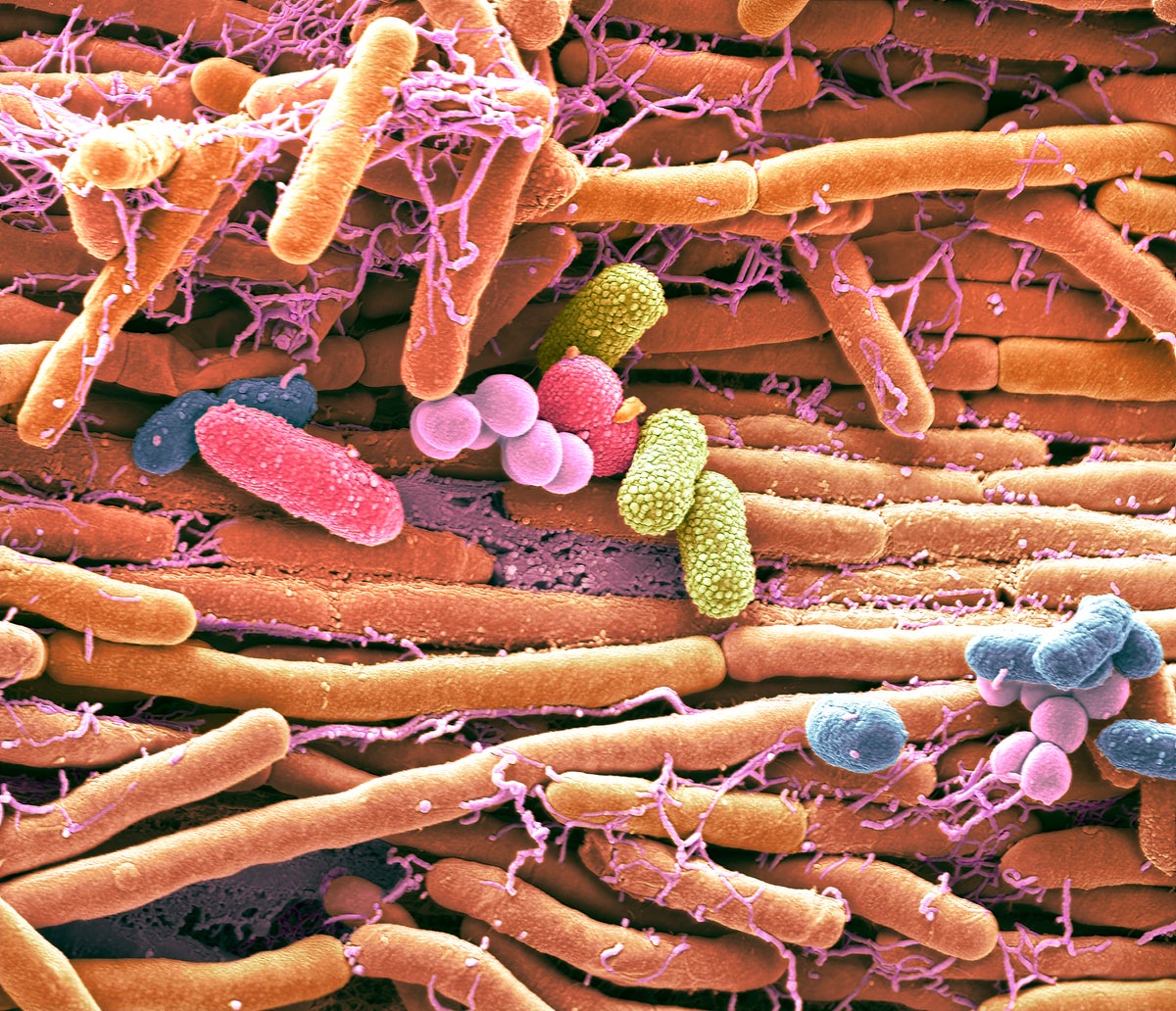

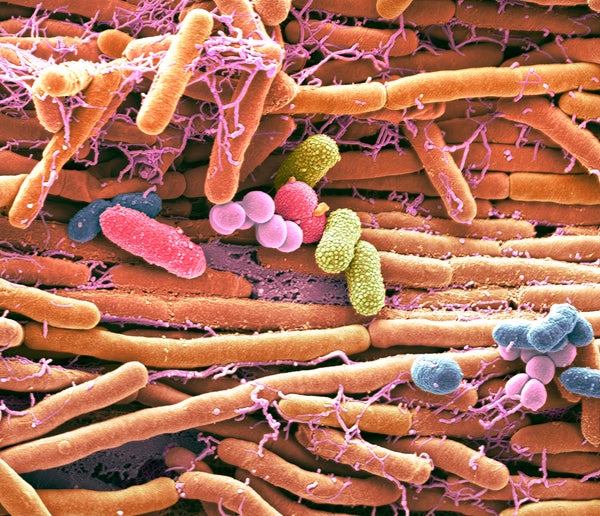

Colored scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of bacteria cultured from a mobile phone. Tests have revealed the average handset carries 18 times more potentially harmful germs than a flush handle in a men’s toilet. With frequent use phones remain warm, creating the ideal breeding ground for bacteria. With touch-screen phones, the same part of the phone touched with fingertips is pressed up against the face and mouth, increasing chances of infection. In tests E. coli, Haemophilus influenzae and MRSA were amongst infectious bacteria found on handsets. Common harmless bacteria include Staphylococcus epidermidis, Micrococcus, Streptococcus viridans, Moraxella, and bacillus species.

Steve Gschmeissner/ Science Source

Most Americans could probably guess that heart disease, diabetes and cancer are among the world’s fastest-growing causes of death. Yet one rapidly accelerating health threat now lurks under the radar, despite its devastating consequences.

The threat comes from antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, the evolved immunity of dangerous microbes to lifesaving drugs. AMR killed 1.27 million people in 2019, more than malaria and HIV combined—according to the most recent comprehensive global analysis. Now, a groundbreaking study published in the Lancet estimates that, without action, AMR will kill more than 39 million people in the next quarter century. Average annual deaths are forecast to rise by nearly 70 percent between 2022 and 2050.

We don’t have to stay on this trajectory. But changing direction will require decisive moves from the U.S. government. As the global leader in pharmaceutical development, the U.S. has a moral obligation to lead the way on solving this global problem. We need to jump-start research and development on new antimicrobial drugs and shore up the patent system that enables us to bring so many new medicines to market.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

AMR occurs when disease-causing microbes—most often bacteria—evolve to evade the drugs created to kill them, turning them into so-called “superbugs.” Some better-known ones include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, a bacterium that causes pneumonia and can be resistant to penicillin. In 1993 U.S. hospitals recorded fewer than 2,000 MRSA infections. In 2017 that number had jumped to 323,000—according to the latest data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preliminary data shows that cases of another superbug called C. auris jumped five-fold between 2019 and 2022.

A major cause of AMR is overuse and misuse of antibiotics. The more a bacterium is exposed to a particular antibiotic, the more opportunities it has to mutate and become resistant. The danger is that as these essential medicines stop working, even minor infections will become hard to treat. That will make even routine surgeries and common illnesses much more dangerous—and make it much harder for those battling cancer whose immune systems are compromised, in particular, to fight off infections. Without action and investment soon to support the development of new antibiotics, we could be thrown back to the pre-penicillin era, when a simple cut could turn deadly.

Yet despite the urgent need for new antibiotics, the pipeline for developing them is drying up. As of today only four major pharmaceutical companies still work on antibiotics, down from dozens just a few decades ago. The reason is simple: the economics of modern antibiotic development don’t work. Creating a single new drug takes an average of 10 to 15 years and costs more than $2 billion. But since antibiotics are typically used for short periods ranging from seven to 14 days and must be used sparingly to limit AMR, their profitability is necessarily low. This built-in roadblock means companies have a hard time justifying the expense and risk.

The new Lancet study recommends several ways to fight back. One of them, unsurprisingly, is to develop new antibiotics—an area in which the U.S. has an opportunity to show global leadership, expand its influence and make an enormous difference.

America has the world’s best system of intellectual property protection, which has made us the global frontrunner in biopharmaceuticals as well as dozens of other high-tech industries. IP protections—in particular patents—provide a window of market exclusivity that allows companies to recoup their enormous investments in research and development. Without reliable patents, few businesses would take the risk of developing new antimicrobial drugs.

Unfortunately, over the last several years, some U.S. lawmakers have advocated for reducing patent protections as a way to reduce drug prices. But these efforts, while well-intentioned, would just make the situation worse. Attacking patents isn’t the right strategy, since it would only create another disincentive to invest in novel antibiotic development. This would likely make it harder to combat outbreaks of infectious diseases and superbugs, which are evolving and growing deadlier each year.

There’s no single panacea for the brewing AMR crisis. It will take action from all stakeholders and segments of society. Everyday Americans, for their part, need to do a better job of letting respiratory viruses like the common cold run their course, rather than asking their provider for antibiotics. Not only are antibiotics ineffective against viruses, attempting to use them to treat viral infections still contributes to resistance. Doctors need to take more responsibility, too. As a physician, I know many of my colleagues could be more judicious in prescribing antibiotics.

Finally, Americans need Congress to be more proactive. One solution to the antibiotic conundrum would be a subscription-type model to incentivize new research and development. Under this kind of system, which is already being tested in the U.K., the government would contract with companies to provide antibiotics for a fixed fee, regardless of how many doses are needed. This would give drug developers a more predictable revenue stream, allowing them to invest in high-risk, high-impact antimicrobial research that saves lives when we need it.

Former secretary of state Madeleine Albright called the U.S. the “indispensable nation,” essential to global progress and peace. Some dispute this characterization, and it’s true that the U.S. can’t solve every problem. But drug research and development is one area where we already lead. Smart policies to tackle AMR can help ensure we maintain this leadership while saving potentially millions of lives worldwide.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.