“Every person is the hero of their own story.”

– Aaron Saguil, MD

Problem:

The demands of medical training continue to put trainees and faculty at a high risk of burnout and mental health issues. Initial responses to this crisis centered around educational approaches. For these approaches, the unit of analysis is the individual. The unstated assumption of educational approaches is that the problem of burnout stems from a lack of awareness or skills at the individual level rather than system factors. A significant limitation of this approach is that it does not address the structural influences that lie outside of the control of the individual trainee. In recognition of this, a second wave of interventions has focused on the environment in which training occurs. Such approaches yield a higher impact, though some institutional cultures resist this change in focus. In an effort to focus organizational attention on these issues, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) included specific wellness-related requirements in both the Common Core Program Requirements (Section VI) and the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) standards.

Gap:

While individual educational approaches and organizational approaches are laudable and necessary, the question arises: Do these approaches have sufficient narrative emotional power to meet the challenges within medical education? Presently, within medical education pursuit of work/life balance, integration, or harmony functions as the centering narrative. Efforts to address excessive work demands include calls for protected time for wellness and time away from work. While in full support of trainee wellness and work-life harmony, one unintended consequence of this focus is the potential to view these categories as dichotomous and at odds with one another- viewing work-related demands exclusively as a threat to wellness and all activities occurring outside of work as automatically nourishing well-being. There is a natural grammar to this approach that knowingly or unknowingly positions work as set against life outside work, setting the two in conflict with each other.

Such a characterization overlooks the potential intrinsic rewards of caring for others’ physical and psychological needs. The ACGME’s Back to Bedside initiative addresses this tension, aiming to foster meaning in the learning environment and help trainees engage more deeply with patients in the course of care. This laudable effort runs into a looming problem in the post-modern world. Namely, it does not provide a narrative architecture to assign meaning and redeem sacrifices attendant to medical training. Aluri, et al. suggest “virtue ethics” as such a centering narrative. They argue that the virtue of altruism develops in response to the “higher claim” invoked by the “good of our patients.” Through this lens, they view sacrifice as an unavoidable “side effect” of medical education. The authors recognize the potential for systems to use the concept of sacrifice to manipulate trainees; they offer guidelines for discerning appropriate limits to sacrifice.

Solution:

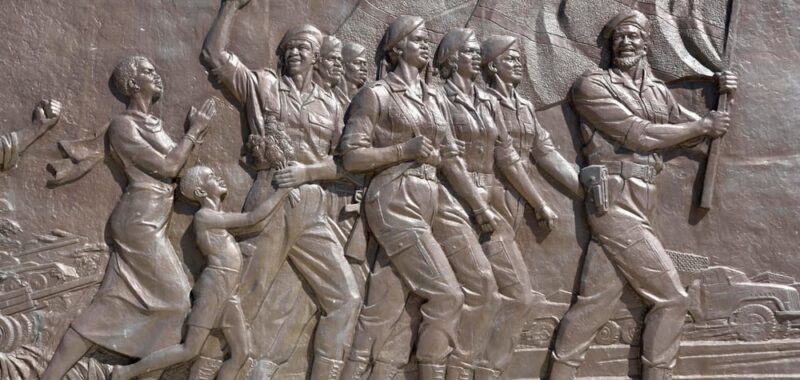

What I propose is an alternate narrative within which to situate and inspire professional identity Formatiof (PIF) during graduate medical education: “the hero’s journey.” In his book, Pathways to Bliss, Joseph Campbell points out that, throughout history, every human culture has transmitted meaning and values through storytelling. Martimianakis et al. explored the important sociologic function of several myths within medical education. They argue that these stories “play important and inescapable roles in the social practice of medical education and the negotiation of values, and in constructing the conditions for group change and transformation.”

Kevin C. McMains is an otolaryngologist.