How Researchers Found a Greener Way to Make Fuel for Nuclear Fusion—By Accident

Researchers have found an environmentally safer way to extract the lithium 6 needed to create fuel for nuclear fusion reactors. The new approach doesn’t require toxic mercury, as conventional methods do

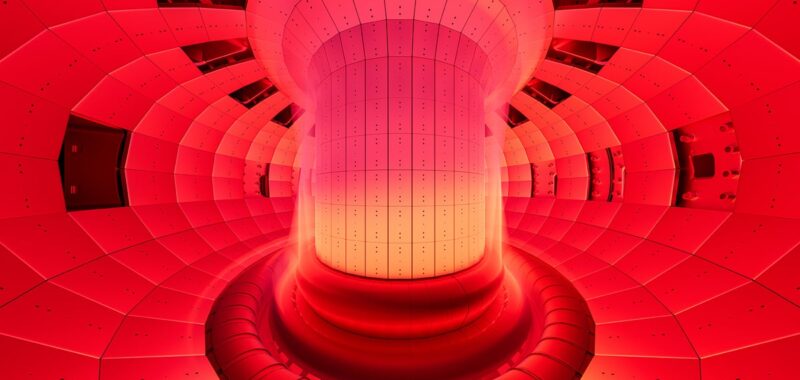

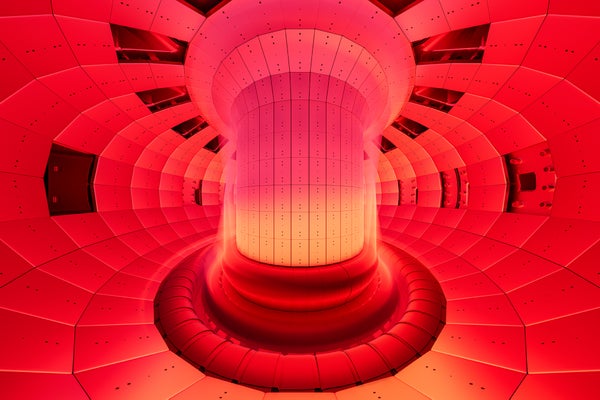

All the nuclear power plants in operation right now use nuclear fission—the process of splitting apart an atom—to produce energy. But scientists have spent decades and entire careers in a frustrating quest to achieve nuclear fusion, which combines atoms, because it releases far more energy and produces no dangerous waste. Many hope fusion could one day be a significant source of carbon-free power.

In addition to the many technical issues that have kept nuclear fusion perpetually in development, the process also needs fuel that presents its own problems. The fuel requires a rare lithium isotope (a version of an atom of the element with a different number of neutrons) called lithium 6.

But the traditional process for sourcing lithium 6 involves using the toxic metal mercury and causes major environmental damage. It has been banned in the U.S. since 1963. The country currently relies on lithium 6 supplies that were stockpiled at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory as part of nuclear weapons development programs during the cold war. “It’s kept a secret how much lithium 6 is left there, but it’s surely not enough to supply future fusion reactors,” says Sarbajit Banerjee, a professor of chemistry at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. Banerjee and his team think they have found a new and environmentally safer way to extract lithium 6 from brine—and they came across it completely by accident.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Nuclear fusion, a reaction that powers stars such as our sun, generates energy by fusing atoms together. In fusion reactors, those atoms are deuterium (a heavy form of hydrogen that is abundant in seawater) and tritium (an even heavier form of hydrogen that is extremely rare but can be bred from lithium 6). Deuterium-tritium fusion unleashes a massive amount of energy—it’s what gives hydrogen bombs their immense explosive power. It also happens at temperatures low enough to be contained in reactors. But it needs a relatively large amount of tritium.

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a 500-megawatt, large-scale experimental fusion reactor that is currently under construction in France, is expected to use much of global reserves of tritium, which are estimated to comprise between 25 and 30 kilograms. To make enough to fuel ITER and other projects, not to mention future fusion reactors, scientists will need much more lithium 6.

When a lithium 6 atom is bombarded with a neutron, it undergoes a nuclear reaction that produces helium and tritium. Because roughly two kilograms of lithium 6 is needed to breed one kilogram of tritium, significant amounts of lithium 6 would be needed for ITER alone. “If nuclear fusion takes off the ground, the demand for lithium 6 will shoot up to thousands of tons,” Banerjee says.

The natural lithium that is now mined from rocks in Australia or extracted from brine deposits in Chile is a mixture of two stable isotopes: lithium 7, which is commonly used in batteries, and lithium 6. The only established industrial process that separates these two isotopes is called column exchange (COLEX): large amounts of liquid mercury flow down a vertical column, while lithium mixed with water flows up. When those two liquids pass each other, the lithium 6 sticks to the mercury a bit more than lithium 7, so it ends up at the bottom of the column, while lithium 7 ends up at the top. But in this process, “a few hundred tons of mercury got released to the environment,” Banerjee says, prompting the U.S. ban.

Thus far, the mercury-free methods for lithium isotope separation have been far costlier and less efficient than COLEX. But then Banerjee and his team went to Texas to work on a seemingly unrelated project: developing membranes for cleaning the water that’s brought to the surface in oil and gas fracking operations.

“We had a couple of membranes that could filter out the oil, salt and silt from the water. At the same time, we were working on some battery materials, so we also filtered out lithium,” Banerjee explains. His team used membranes made from zeta vanadium oxide, a patented material the team synthetized in a lab. The membranes contain a framework of one-dimensional nanoscale tunnels—and the team found these tunnels were particularly good at capturing lithium ions. They could even separate lithium 6 from lithium 7.

To test this process more thoroughly, the researchers built an electrochemical cell: a sort of battery working in reverse. When water was cycled through the powered-up cell, positively charged lithium 6 ions got trapped in the one-dimensional tunnels of the negatively charged zeta vanadium oxide electrode. But heavier lithium 7 ions were more likely to break the bond with the tunnels and mostly avoided getting stuck in them. The results were published on March 20 in Chem.

The technique could reach the level of enrichment suitable for nuclear fusion fuel after 25 four-hour cycles, Banerjee and his team say. Another plus was that zeta vanadium oxide gradually changed color from yellow to dark green when more lithium ions got trapped in it, which provided a very clear indicator of when the job was done. To get the lithium out of the cell, Banerjee’s team simply reversed the polarity to push trapped ions out of the tunnels and back to the circulating water.

“This method seems to have excellent separation, which is very promising”, says Norbert K. Wegrzynowski, a physicist at the University of Bristol in England, who has worked on isotopic separation of lithium 6 and is not affiliated with Banerjee’s team. “However, the next question is scalability. The key problem for such methods is driving the cost down enough to make them cost effective,” Wegrzynowski says. He believes, though, that techniques along these lines may be the easiest and fastest to scale up to an industrial level.

“The efficiency of this process is already comparable to COLEX, and it’s just an unoptimized proof of concept. Within six months or so, we can probably be doing much better” Banarjee says. He believes his lithium isotope separation technique could be implemented at an industrial scale within a couple of years. “The materials to make this work are available, and it’s not the hardest process in the world,” Banerjee says. “It’s not that far from actual realization.”