When Texas passed a 2021 law banning nearly all abortions after detection of fetal heart activity—typically around five to six weeks of pregnancy—Jason Darr, a now 46-year-old Texan, began researching a procedure he’d considered off and on for years: a vasectomy. He’d wanted kids when he was younger, but circumstances hadn’t made that a reality, and he didn’t want a newborn as he approached his 50s.

Later that year the Supreme Court heard arguments for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, and in June 2022 the justices overturned Roe v. Wade, leaving laws about abortion up to individual states. Since then nearly a dozen U.S. studies have shown that Americans’ interest in permanent contraception—both vasectomies and tubal sterilization procedures such as tubal ligation—spiked in the months after Dobbs. And more and more people have been seeking permanent sterilization in the wake of the decision. The rate is higher across the board, but new studies show the increase is especially sharp among men.

“It was the Texas law that really got me looking into the burdens of contraception and how we put such a burden solely on women for being 100 percent responsible for the entire realm of contraception—and that’s kind of crappy,” Darr says. Overturning Roe was the final straw for him.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

After Darr learned that a vasectomy (surgery that severs and seal vas deferens ducts to prevent sperm from leaving the testes) was covered by most insurance plans—and saw that abortion was becoming more regulated in Texas—he concluded that “it’s going to be a crap-load easier if a guy just gets snipped versus having to deal with something after the fact.”

Darr had his consultation early in 2024. In May of that year, two years after a draft of the Dobbs ruling was leaked, he had the vasectomy.

“Often reproductive health and contraception falls on the partner with a uterus,” says Jessica Schardein, a urologist at the University of Utah. “So seeing the other partner step up and take responsibility to ensure there is no unintended pregnancy highlights how reproductive health matters to all people, even those without a uterus.”

A Swell of Interest

Darr isn’t alone in seeking a permanent form of contraception post-Dobbs.

Kara Watts, a urologist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City, published data several months after the Dobbs decision showing that Google searches for information on vasectomies increased significantly in the three months after the ruling compared with the three months before it—especially in states where abortion became illegal, such as Oklahoma, Utah and Idaho.

“While the overruling [of Roe] directly impacted women’s reproductive rights, the immediate downstream impact on men’s consideration of their access to, and right to, elective forms of sterilization was [also] impacted,” Watts says.

The Google search results accurately predicted a surge in procedures. When Watts studied vasectomy consultation rates among men at eight academic medical centers around the U.S., she found the rate of vasectomies that occurred after consultations increased from 152 cases per month in the year and a half before Dobbs to 158 cases per month in the six months after the decision. And the men seeking vasectomies after Dobbs were also an average of two years younger and had fewer children. The trend among single, childless men seeking the procedure was even more notable: the proportion was nearly twice as high after Dobbs (about 40 percent) as before the ruling (about 23 percent). (These results were presented at the latest annual meeting of the American Urological Association in May.)

“Two years later, the impact is still present,” Watts says. “In our country, where practicing urologists are a growing scarcity, our ability to meet the needs of men seeking vasectomies, in balance with all other urologic needs, may continue to be a challenge.”

And it’s not just vasectomies—more people who can become pregnant are seeking permanent surgical sterilization and not only in states with harsh abortion regulations.

Not Just Vasectomies

Sarah Prager, an ob-gyn and family planning specialist at the University of Washington, says she saw “about a 10-fold increase” in people seeking a tubal sterilization procedure in the three months after Dobbs, despite abortion remaining well protected in Washington State.

“People were just universally very freaked out and wanting to be very certain that they wouldn’t be faced with an unwanted pregnancy they couldn’t manage,” Prager says. Many were students or others who expected to be moving around the country.

“What’s happening in another state can very well impact them in the future, so I think people didn’t feel as much security living in Washington as you might expect,” she says. Though demand has settled down since then, Prager says her clinic still receives more requests for sterilizing procedures than it did before Dobbs.

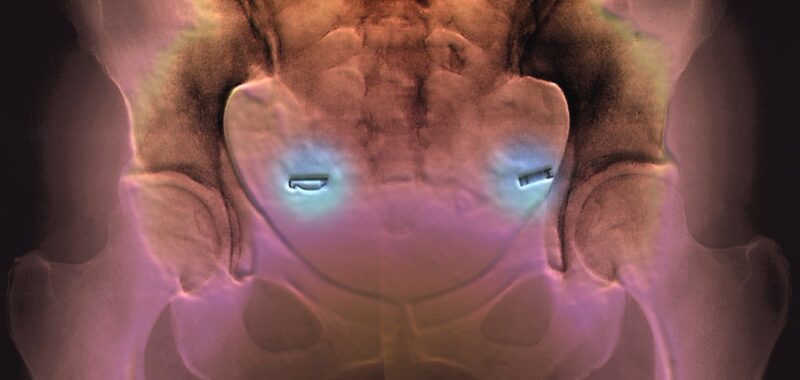

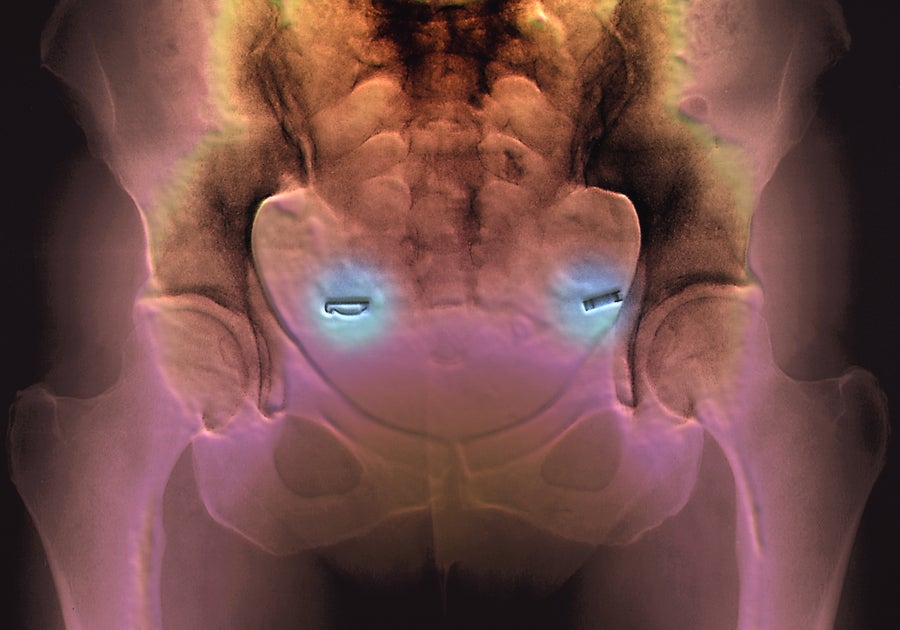

Pelvic X-ray of a patient with tubal ligation clips on their fallopian tubes, stopping eggs traveling from the ovaries to the womb and preventing them from being fertilized by sperm.

Schardein found similar patterns when she analyzed the medical records of 217 million people in the U.S. to compare tubal sterilization and vasectomy rates in the last six months of 2021 with rates in the last six months of 2022—just after the June 2022 ruling.

Among those under age 30, vasectomy rates increased by 59 percent, and tubal sterilization rates increased by 29 percent. Vasectomy rates increased 13 percent among single men, while the rate of tubal sterilizations among single women did not change. Vasectomy rates rose in nearly all states, but tubal sterilization rates increased slightly more in states where abortion became illegal.

Linda Shiber, a gynecologist at MetroHealth in Cleveland, found comparable trends among people seeking tubal sterilization at her institution. In comparing the year before Dobbs to the year after, not only did that number increase—especially in the three months after the decision—but more people without children and people aged 21 to 25 sought such procedures. Shiber conducted the study, which was presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Annual Clinical & Scientific Meeting in May, after receiving a swell of requests for a tubal sterilization procedure from people in that age group.

She says many of those who came to her had already been using highly effective contraception, but they were anxious that new laws could potentially restrict options in the future. “As safe abortion access is progressively curtailed in this country, we will see a trend toward utilization of surgical sterilization as a primary contraceptive method in younger women who do not want children,” Shiber says.

Grace Rossow, a 32-year-old surgery case coordinator in central Illinois, is one of those women. Rossow contracted polio as an infant in India in 1992, and her doctor later told her having children could be risky. “That wasn’t the life I wanted,” she adds. She had used an IUD for birth control since graduating college, but the Dobbs ruling came just as it was time to replace the device.

“I’d thought about having a tubal [sterilization], and Dobbs just was the final nail in the coffin,” Rossow says. She ultimately had a bilateral salpingectomy—removal of the fallopian tubes, which carry eggs from the ovaries to the uterus—which also reduced her risk of ovarian cancer. Though she lives in Illinois, where abortion is protected, “if I ever live in a state without abortion protections, I know I am still protected from pregnancy,” Rossow says.

Young Adults Are Most Concerned

Other studies have also found jumps in both vasectomies and tubal sterilization procedures after Dobbs, particularly among younger, single individuals.

Jacqueline Ellison, a health policy researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, specifically investigated sterilization rates in younger adults in an April 2024 study. In the paper, she and her co-authors noted people in this age group “are more likely to have an abortion and to experience sterilization regret.”

Ellison analyzed national medical records data for 2,854,071 women and 1,981,996 men aged 18 to 30 for the period before Dobbs (January 2019 to May 2022) and after (June 2022 to September 2023).

Ellison found that tubal sterilization rates have been increasing among younger women—by about five procedures per 100,000 people per month. Vasectomies among young men also increased post-Dobbs.

The study can only show correlation, not the cause of the rise. But Ellison says she’s “pretty confident that the increase is directly a consequence of the Dobbs ruling” because “there’s no other event that happened around that time that would have caused that spike.”

Sterilization regret is a real phenomenon—and tends to be higher in women under 30—but younger women may find it difficult to get a sterilization procedure because of some physicians’ “paternalistic concerns” about regret, Ellison says. At the same time, the U.S. already has a sordid history of forced sterilizations, and the current trend of increasing voluntary ones appears influenced by pressure related to the difficulty of getting an abortion in many places. That difficulty includes increased costs of travel and care, particularly for racially or ethnically marginalized populations. And the Dobbs decision will exacerbate existing inequities, Ellison says. She adds that she has heard this trend referred to as “legislative coercion” because people are undergoing a permanent, invasive procedure they might not otherwise have undergone.

“People are afraid and anxious about restricted access to abortion and contraception down the road,” Ellison says. “People shouldn’t feel pressured to undergo this procedure because of a Supreme Court decision or the legislative environment.”