On the morning of May 8, 1845, residents of Juneautown, the settlement east of the Milwaukee River, woke up to find the Chestnut Street drawbridge ― which connected the community to the westside Kilbourntown settlement across the river ― had been destroyed. Much of what remained was now in the river.

The bridge, which once stood at present-day Juneau Avenue, “floated in a stately fashion downstream, and the east-siders woke up to find they couldn’t get over to the west side,” said Milwaukee historian John Gurda.

The east-siders knew exactly who was to blame: Kilbourntown. Enraged, the citizens of Juneautown gathered “a small arsenal of weapons,” wrote Milwaukee author and historian Matthew Prigge in a “Shepherd Express” feature. The east-siders’ arms included an old cannon loaded with clock weights that they planned to fire at the home of Byron Kilbourn, Kilbourntown’s ambitious, disagreeable founder and leader.

What would cause citizens to wreak havoc on infrastructure within their own neighborhoods? Well, as Gurda puts it, it’s a “story of excessive ambition, complete lack of collaboration, selfishness, greed and a cup boiling over into violence.”

This is the story of Milwaukee’s Bridge War ― how a bitter feud between local founding fathers boiled over into property destruction … and eventually may have united the city.

Milwaukee’s founding fathers: Juneau, Martin, Walker and Kilbourn

Before Milwaukee was Wisconsin’s largest city, it developed as multiple sectional communities, like many early settlements.

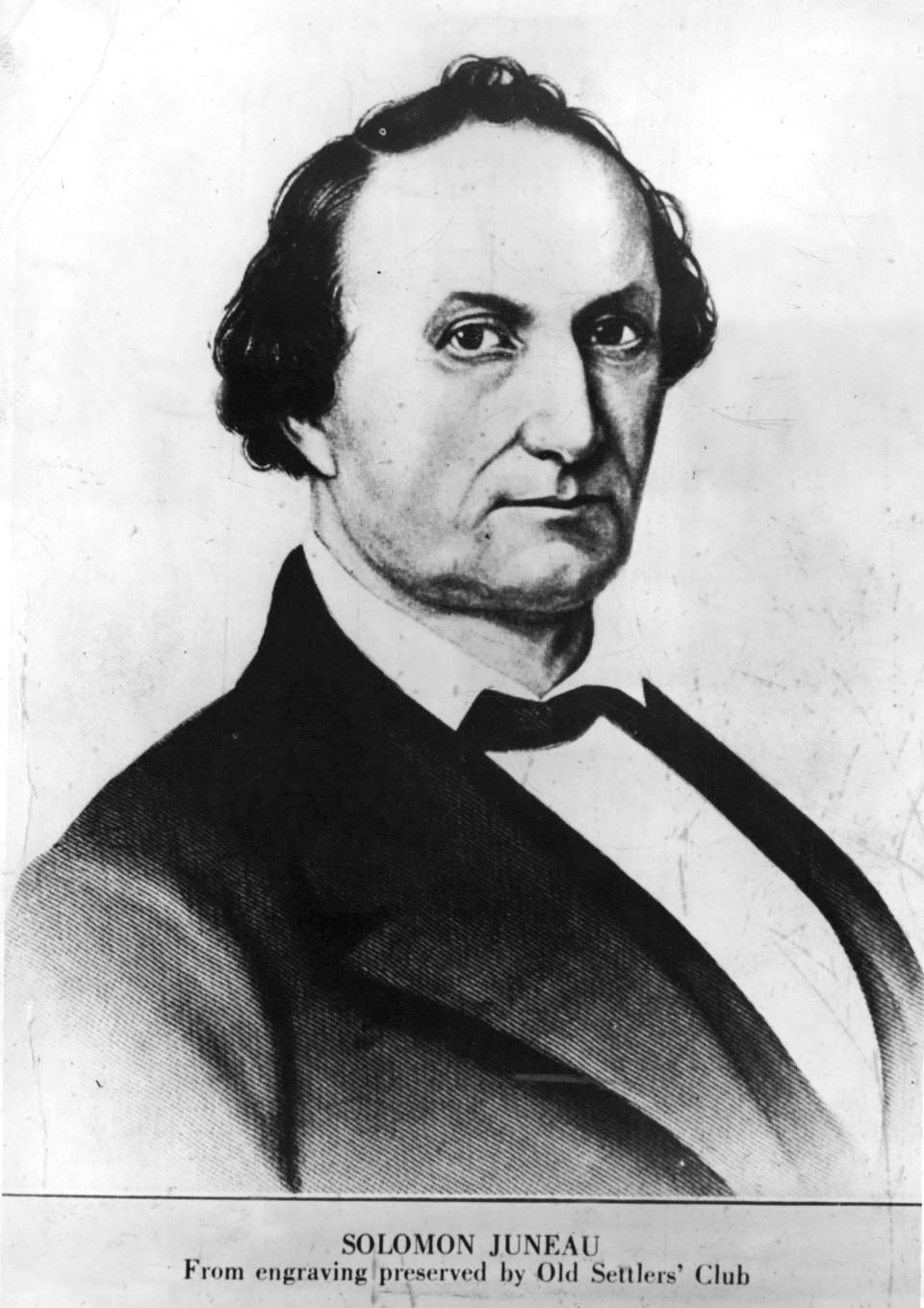

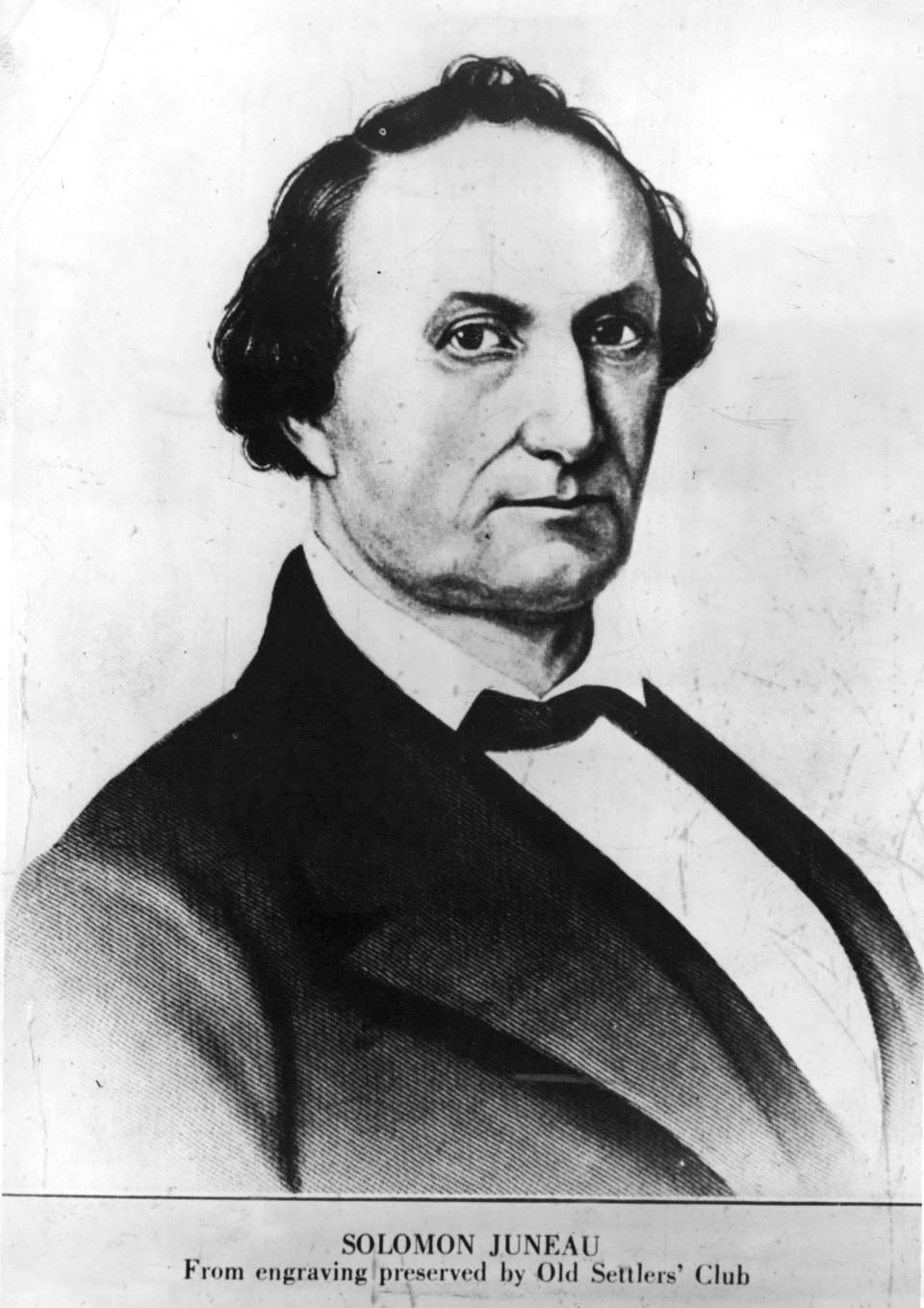

The first of these, established in 1818, was Solomon Juneau’s Juneautown on the east side of the Milwaukee River. Gurda described Juneau, a successful fur trader from Montreal, as more laid-back than his business partner Morgan Martin. Martin, an “aggressive, eastern, Yankee capitalist,” had the “skills, political connections and access to capital, but Juneau had the claim” to the land, Gurda said.

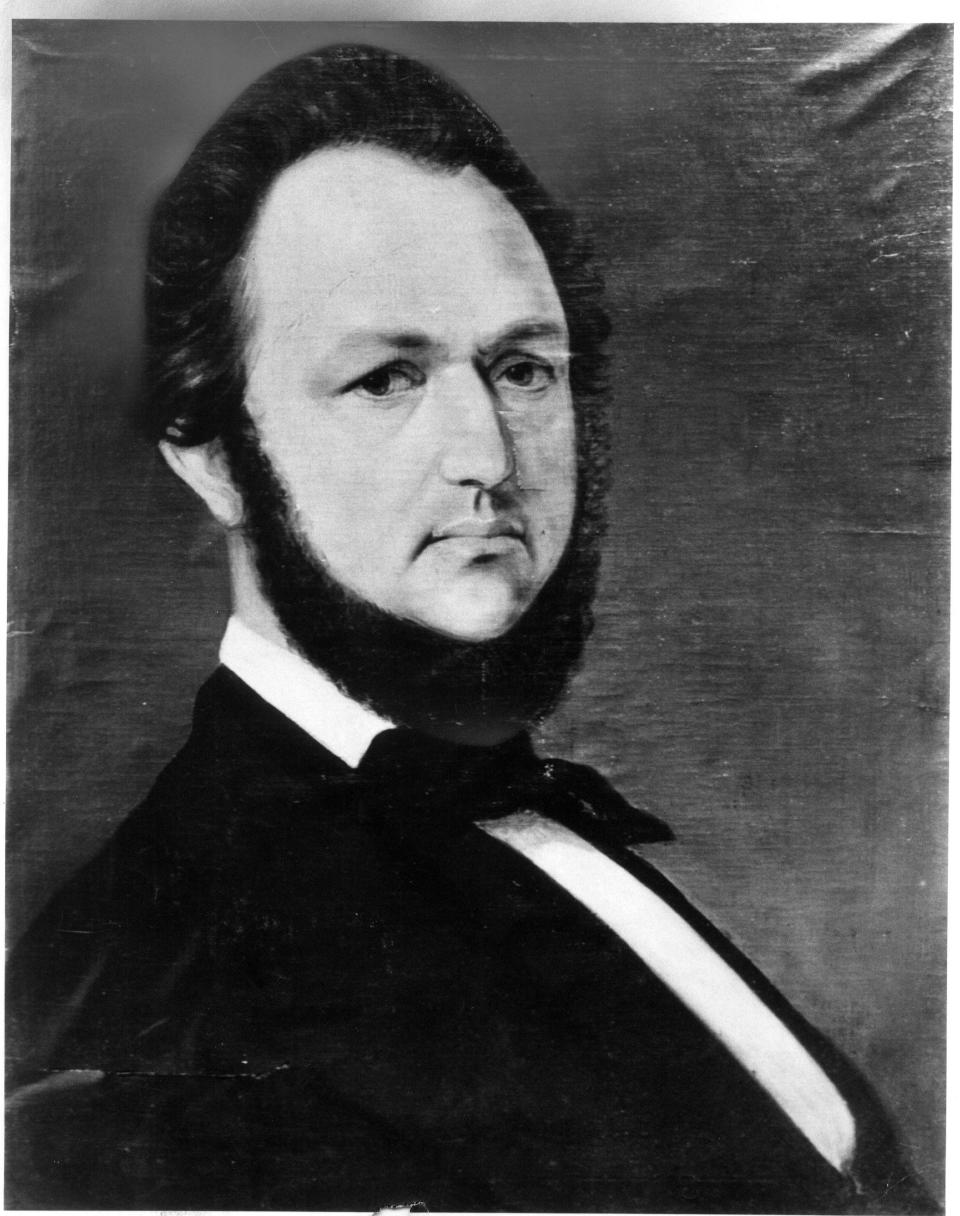

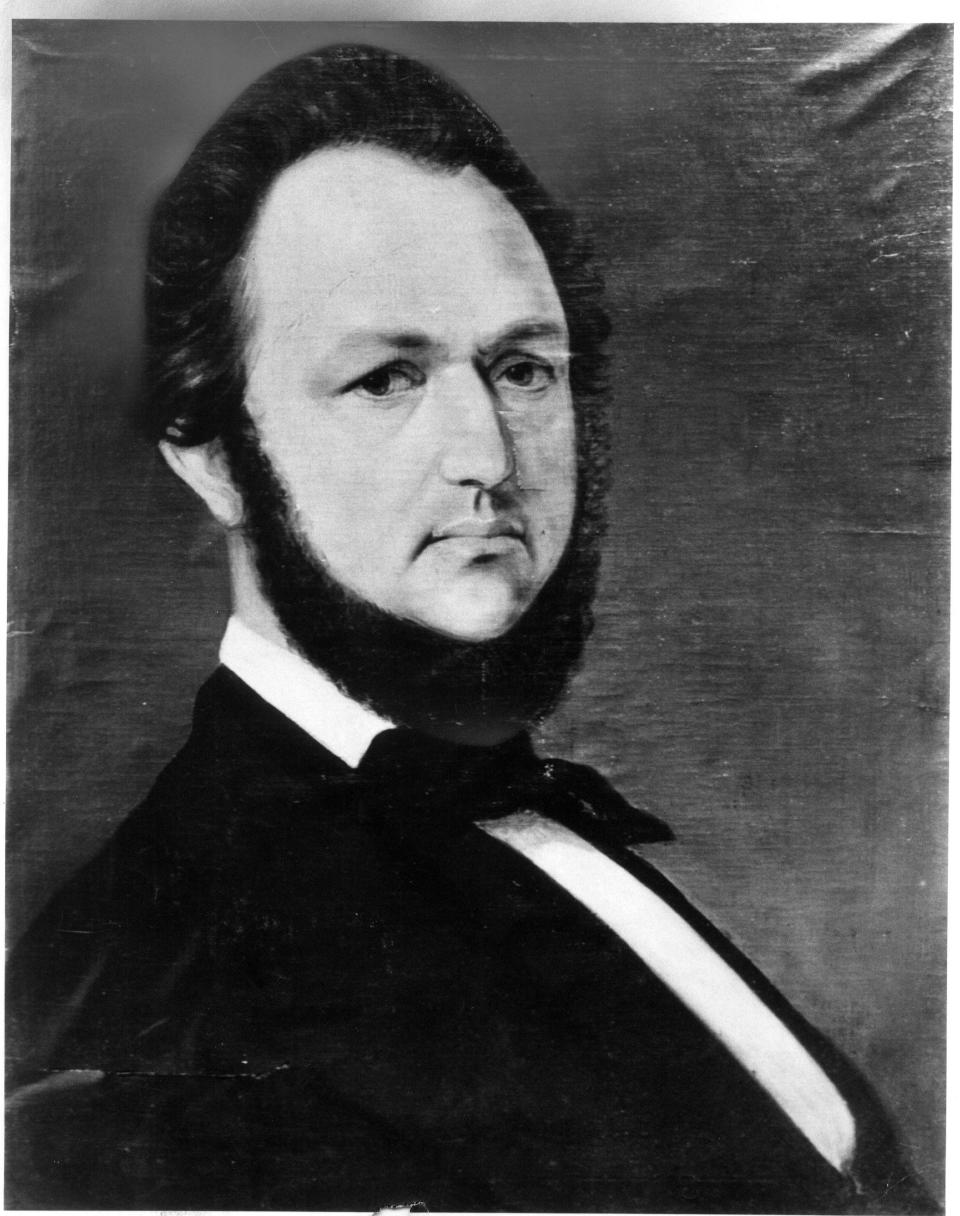

In 1834, George Walker established Walker’s Point to the south and Byron Kilbourn founded Kilbourntown west of the river. Because his settlement was smaller and less resourced than the east-west rivals’, the jovial Walker was often seen as a “distant third” among Milwaukee’s founders. Kilbourn, meanwhile, had “down-turned lips and stern eyes,” Gurda said. “He really was not a guy you’d want to play cards with.”

A land surveyor and canal boss from Ohio, Kilbourn had “delusions of grandeur and becoming the ‘King of the Midwest,'” Gurda said. He “vigorously” advocated for a canal that would link the Milwaukee River with the Rock River and eventually the Mississippi. However, the Wisconsin Territorial Legislature pulled support for the project.

Kilbourn also sought to dominate the Milwaukee River settlements. When laying out Kilbourntown’s street grid in 1835, he disregarded the streets Juneau had already built.

“Aligning the roads would have meant acknowledging the viability of Juneautown, something Kilbourn was loath to do,” Prigge wrote.

Kilbourn’s declaration that his settlement was separate from Juneau’s is still evident today in the angularity of downtown’s Milwaukee River bridges, especially those at present-day Wisconsin Avenue (the site of the former Spring Street bridge) and Wells Street (where the Oneida Street bridge once stood).

Kilbourn hoped to direct traffic toward his settlement and away from Juneautown, thereby bolstering Kilbourntown’s economy. At the time, the east-siders seemed to have the upper hand; they had a larger population, the post office, the land office and the courthouse.

Still, an advertisement map created by Kilbourn portrayed Juneautown as a “barren wasteland,” wrote UW-Milwaukee history professor Lex Renda.

This embedded content is not available in your region.

Tensions rise as bridges are built

Despite Kilbourn’s disinterest in connection, in 1840, Juneautown succeeded in having the territorial legislature require the construction of the Chestnut Street bridge. This was the only Bridge War-era bridge constructed with public funds, and it was “just downstream from Kilbourn’s house,” adding insult to injury, Gurda said.

Over the next few years, the other bridges were built with funds from local capitalists at Spring Street in 1842 and at Oneida and Water Streets in 1844. Kilbourntown also constructed the Menomonee River bridge, which directly connected their settlement to the road to Chicago, allowing travelers to bypass the ferry service that ran between Walker’s Point and Juneautown, Renda wrote.

According to Renda’s account, Kilbourn attested that the Chestnut, Oneida and Water bridges “interfered with river traffic and his ferry docks.” Kilbourntown settlers also disliked paying taxes to build and maintain the poorly constructed Chestnut bridge, despite east-siders actually paying for the bulk of bridge maintenance.

Bridge War breaks out and (eventually) unites Milwaukee

What came to be known as the “Milwaukee Bridge War” likely started on May 3 ― nearly a week before Kilbourntowners brought down the Chestnut Street bridge ― when a schooner rammed into the Spring Street bridge. Rumors swirled in Kilbourntown that the east-siders, angered by the west’s opposition to virtually all other bridges, had bribed the captain to damage the west’s favored bridge.

Four days later, at an emergency meeting of village trustees, Kilbourntown representatives declared the Chestnut Street bridge an “insupportable nuisance” and said they “held the authority to remove such impediments located within their ward,” Prigge wrote. However, other trustees rejected this proposal, so the Kilbourntown mob took things into their own hands.

On May 8, in addition to destroying the Chestnut Street bridge, the west-siders damaged the Oneida Street bridge.

After gathering weapons to strike back, the east-siders decided to hold fire after learning that Kilbourn’s young daughter had died.

Soon, village trustees passed a resolution imposing a $50 fine on anyone who destroyed a bridge. They also ordered the reconstruction of the Chestnut bridge and the abandonment of the Oneida bridge in order to use its pieces to repair the Spring structure.

But Juneautown didn’t let Kilbourntown off without retaliating. On May 28, the east-siders destroyed the Spring Street bridge, one of two bridges in town that Kilbourn had not opposed the construction of, since it gave Kilbourntown residents direct access to the post office and courthouse on the river’s east side, Renda wrote.

Rifle shots “rang out in celebration” as citizens of Juneautown watched the Spring Street bridge fall into the river, Prigge wrote. East-siders also damaged the Menomonee River bridge, which connected Kilbourntown to Walker’s Point.

By the end of May 1845, the recently established village of Milwaukee was home to just one intact bridge on Water Street, and four that were either damaged or destroyed.

Tensions continued to run high. Although there were not believed to be any casualties in the Bridge War, bloody assaults were reported on both sides following the bridge-destroying incidents. By early June, village trustees ordered all bridge work to be done with an armed guard present, according to Prigge’s account.

As summer turned to fall, people on both sides of the river began to realize that the chaos of the Bridge War was scaring prospective settlers away from the area. Settlements throughout Wisconsin were “on the make,” and there was no guarantee Milwaukee would grow to be the largest in the state, Gurda said.

“The rivalries were fairly fierce, but the awareness that they were essentially shooting themselves in the foot was a powerful incentive to cooperate,” he said.

In December, village trustees applied to the legislature for a city charter. They also elected to rebuild an improved Spring Street bridge, erect a new bridge at Cherry Street and update the Water Street bridge.

On Jan. 5, 1846, the charter was approved, establishing the City of Milwaukee and uniting Kilbourntown, Juneautown and Walker’s Point. But, this didn’t mean sectional differences magically melted away. Kilbourntown and Walker’s Point voters “almost unanimously favored” the charter, 461 to 8, while east-siders, “who feared bearing the brunt of taxation and remained bitter over bridge conflict,” voted against the charter 324 to 182, Renda wrote.

Still, the incorporation of the city was finalized on Jan. 31, and, with 9,660 residents, Milwaukee became the largest settlement in Wisconsin Territory, two years before Wisconsin statehood.

The Bridge War’s lasting legacy

Beyond the visually obvious crooked Milwaukee River bridges, the Bridge War had other impacts that far outlived Kilbourn and Juneau.

In many ways, joining the city together was a “papered-over marriage,” and sectional differences prevailed, Gurda said. When Milwaukee became a city in 1846, it was divided into five wards, which each enjoyed considerable political autonomy, controlling their own public works budgets and school boards, Gurda said.

Over time, as the need for a city hall, larger courthouse and other complex projects arose, there was intense disagreement about which side of the river they should be on. The south side remained smaller and, therefore, lacked the votes to achieve much influence, but the east and west sides were fairly evenly matched, especially as the west grew, Gurda said.

City Hall was built in 1895 east of the river, and the Milwaukee County Courthouse was completed on the west side in 1931, showing that sectional conflicts were still alive and well nearly a century after the Bridge War.

The east side became Milwaukee’s “business center,” home to its banks and insurance companies, while the west “lagged behind for a long time in terms of property values,” Gurda said.

However, the west has “enjoyed a renaissance” in recent decades with the opening of the Grand Avenue Mall in 1982 and the Deer District’s explosive growth.

In 1972, legal changes in Wisconsin required Milwaukee’s wards to be transformed into aldermanic districts. However, alderpersons still have “a lot of say” over their districts, Gurda said, a reflection of the city’s sectional past.

What’s What the Wisconsin?

Is there something about Milwaukee or Wisconsin that’s been puzzling you? We’ve got experts who know how to find answers to even the smallest (and sometimes the most interesting) questions. When we can, we’ll answer with stories. Submit your question at bit.ly/whatthewisconsin.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: 1845 Milwaukee ‘Bridge War’ left mark of crooked bridges, united city