JWST Spots Remains of Alien Planet That Fell into a Star

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope provided a closer look at the aftermath of a star that wreaked violence on its planet

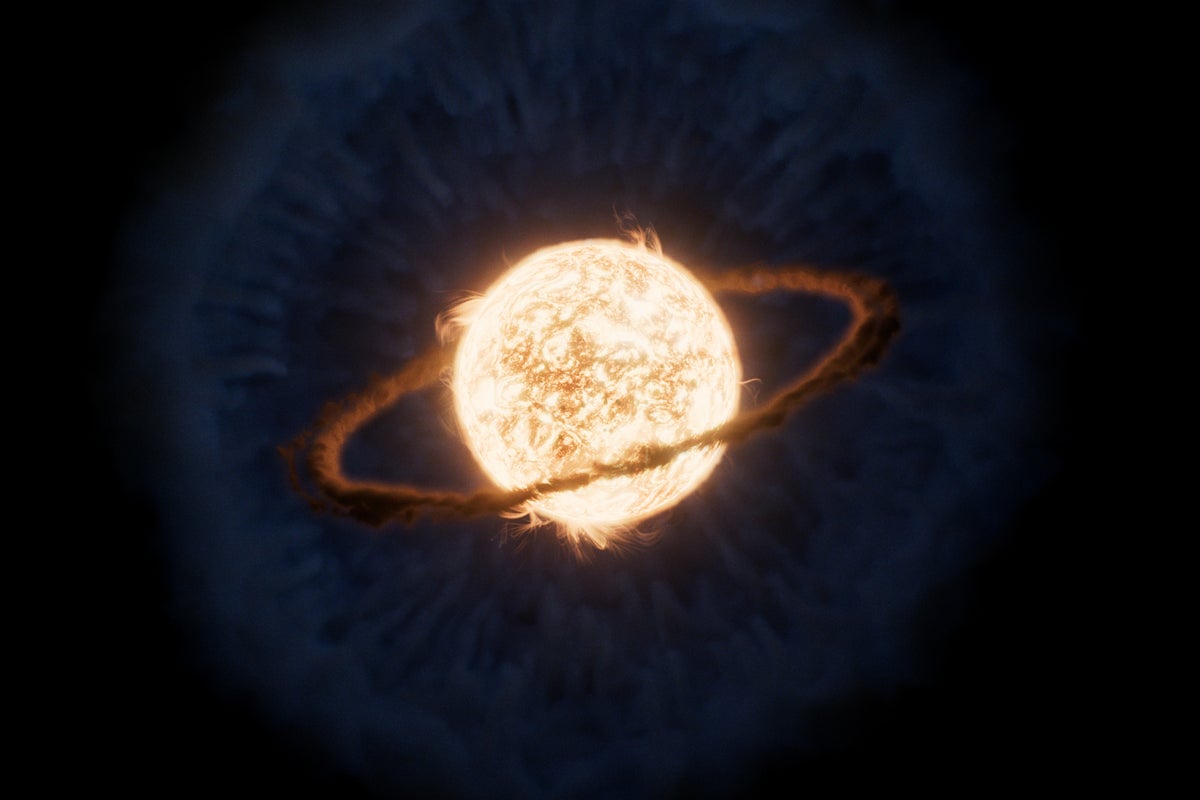

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has followed up on what is thought to be the first known observations of a star engulfing a planet. This artist’s concept depicts a ring of hot gas left by the event around the star and an expanding cloud of cooler dust enveloping the scene.

NASA, ESA, CSA, R. Crawford (STScI)

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has determined that a discovery that could be likened to a cosmic crime scene isn’t what astronomers thought: rather than pointing to a star that swelled up to swallow its planet, the finding seems to reveal that the planet spiraled into its own sun.

The Background

In 2020 astronomers spotted an intriguing event that they labeled ZTF SLRN-2020. Over about 10 days, optical light from a certain location in our galaxy spiked, then faded over about six months. When scientists started investigating, they found that data from another telescope, called NEOWISE (Near-Earth Object Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer), showed that this galactic neighborhood had begun glowing even more brightly in infrared light about seven months before the optical light began—and that this lasted for more than a year.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The researchers also pinpointed the light to a Milky Way star about 12,000 light-years away from Earth. And they suggested that the drama indicated that a sunlike star absorbed a planet less than 10 times the mass of Jupiter. That’s a very reasonable scenario—and one scientists already expect to play out in our own solar system some five billion years from now, with our sun ballooning up and absorbing at least the innermost planets.

What’s New

More than two years after the initial outburst, researchers (including some of the scientists who conducted the original study) arranged for JWST to turn its piercing vision on ZTF SLRN-2020 using two key instruments: the telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec). Their observations change the story of this strange event in intriguing ways, the scientists reported on Thursday in the Astrophysical Journal.

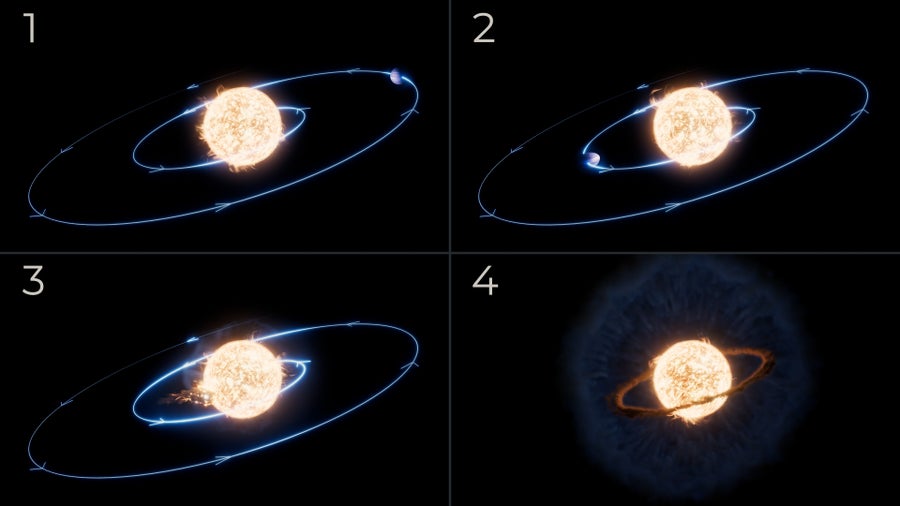

Illustrations show an artist’s depiction of a planet (orbit shown in light blue) falling into a star. The NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope’s observations of what is thought to be the first ever recorded planetary engulfment event revealed a hot accretion disk surrounding the star (shown in brown), with an expanding cloud of cooler dust enveloping the scene (in blue). JWST also revealed that the star did not swell to swallow the planet, but the planet’s orbit actually slowly decayed over time. The star is located in the Milky Way galaxy about 12,000 light-years away from Earth.

NASA, ESA, CSA, R. Crawford (STScI)

First, MIRI determined that the star wasn’t bright enough to be a red giant, a type of star that forms when a sunlike object swells up. That means the star couldn’t have engulfed its planet directly, as originally proposed. Instead scientists now think that the planet was originally about the size of Jupiter but orbited closer to the star than Mercury orbits our sun. Eventually it slipped too close and began to inexorably fall into the star.

During the final merger, scientists think the plant’s impact sent gas from the star’s outer layers flying into space, where it cooled and became a large halo of cold dust. But surprisingly, NIRSpec also identified a thin ring of molecular gas closer to the star, complicating scientists’ understanding of how planets meet their demise.

“This is truly the precipice of studying these events. This is the only one we’ve observed in action, and this is the best detection of the aftermath after things have settled back down,” said the new study’s co-author Ryan Lau, an astronomer at the National Science Foundation National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NSF NOIRLab), in a recent NASA statement. “We hope this is just the start of our sample.”

More from JWST

Here at Scientific American, we’re also excited about plans for JWST’s fourth year of observations, which begin this summer. Exoplanet-related work will tackle questions that include whether habitable worlds can be found orbiting stellar corpses known as white dwarfs. JWST will also examine whether a handful of particularly interesting exoplanets have an atmosphere, a characteristic that is important to the plausibility of finding life on such worlds.