JWST Spots Giant Spiral Galaxy Shockingly Early in Cosmic History

Nicknamed the “Big Wheel,” a giant, spiral-shaped disk galaxy was spotted in an unusually crowded part of the early universe just two billion years after the big bang

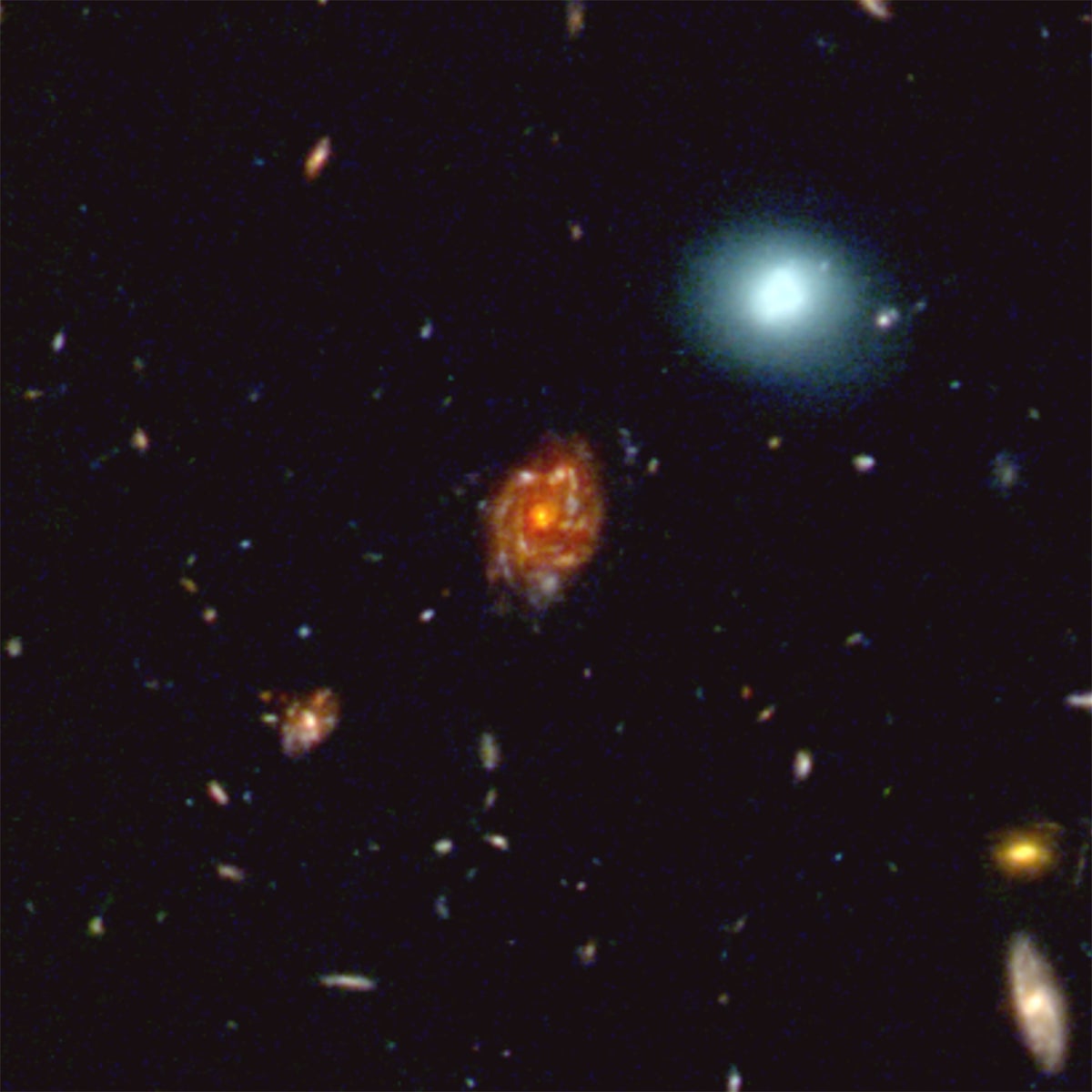

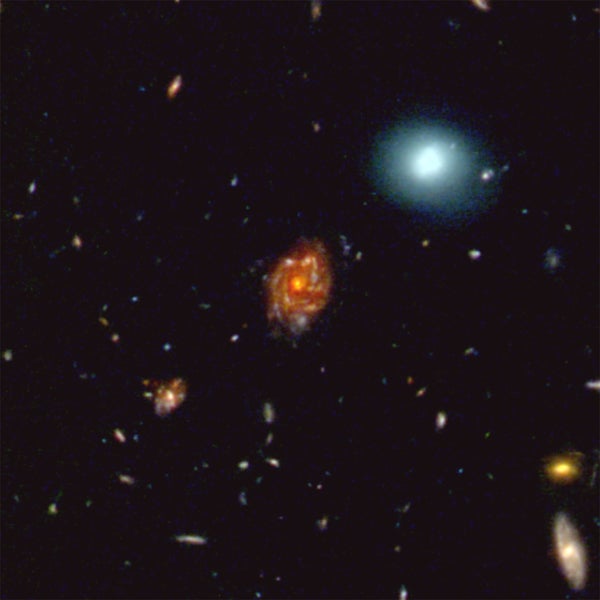

A giant spiral galaxy, nicknamed “Big Wheel,” as seen by the James Webb Space Telescope from some two billion years after the big bang. Big Wheel’s starry disk stretches across more than 100,000 light-years, making it larger than any other galaxy disk confirmed from this cosmic epoch.

Weichen Wang/Sebastiano Cantalupo/ESA/NASA

A newfound object uncovered in the early universe by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is challenging long-held ideas about how galaxies form. Dubbed the “Big Wheel,” it’s a galaxy much like our own Milky Way—a humongous, spiraling disk of stars, gas and cosmic dust. But Big Wheel is even bigger than our home galaxy; it’s some five times more massive and covers twice as much area.

And the weirdest thing of all about Big Wheel isn’t even its size but rather its age. JWST has seen it from when the universe was only about two billion years old, which is remarkably young for a galaxy of such grandeur.

Typically it should have taken the whole age of the universe for a galaxy to have grown so large, says Sebastiano Cantalupo, an astronomer at the University of Milan-Bicocca in Italy, who co-authored a recent Nature Astronomy paper about the discovery. Compared with its much smaller, more nascent contemporaries in that bygone era, “you can clearly see Big Wheel is a true outlier,” he says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The discovery is part of a broader trend in astronomy, as ever-larger and more capable telescopes look deeper into the universe, gathering light from cosmic vistas further and further back in time. Using JWST and other powerful facilities, observers have been able to glimpse some early galaxies just a few hundred million years after the big bang, says Vadim Semenov, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. Semenov, who was not involved in the new study, notes that Big Wheel is “one of the most extreme examples” of galaxy formation in the early universe, when that process was expected to be “far more vigorous and chaotic, driven by frequent galaxy mergers and the rapid accretion of material from intergalactic space.”

All that primordial intensity comes from the small size of the early universe, which had a higher density of the raw materials from which galaxies coalesce. But the neighborhood where Big Wheel lives is packed with an exceptional overabundance of matter even for that already-enriched cosmic epoch. That’s probably where it got to indulge in a “heavy breakfast,” says Chuck Steidel, study co-author and an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology. According to Steidel, Big Wheel is somewhat like “a child that started off as the biggest on the block and ate everybody else’s breakfast…. It looks like an adult galaxy at a time when there were only supposed to be children around.”

The study’s lead author Weichen Wang, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Milan-Bicocca, was the first to notice Big Wheel in JWST’s data. He initially thought the galaxy was an unhelpful distraction to his other, unrelated studies of this particular patch of the early universe. The giant spiral didn’t look like it belonged there, so Wang assumed it was an interloper from much later in cosmic time that just happened to be in JWST’s field of view. Upon further analysis, however, Wang and his colleagues were able to gauge Big Wheel’s true cosmic distance, and they suddenly realized that the object they were seeing was in fact a faraway galaxy “that has grown really, really fast since the beginning of the universe,” he says.

But it’s still unclear how exactly Big Wheel got so big so quickly. Matter pouring into growing galaxies tends to spark intense outbursts of radiation from rapid bouts of star formation and the voracious feeding of accompanying central black holes; such outbursts can cut off the flow of infalling matter, pushing material away from the forming galaxy and stifling further growth. “At the moment, I have to say it’s a mystery—a complete mystery,” Cantalupo admits. Perhaps, he says, Big Wheel’s crowded environment may have allowed for “some previously unknown physical mechanisms that [help] galaxies to grow.”

Semenov offers a gardening analogy: “It is like entering a garden in spring and discovering a perfectly ripe fruit you would expect in late summer,” he says. “To determine whether existing models can explain such galaxies, we need detailed theoretical and numerical studies that capture both the extreme galaxies and the extreme environments they inhabit.”

So, given that we’ve seen Big Wheel as it was some 12 billion years ago, what can we say about its status today, in our current cosmic era? Not very much of certainty, Steidel says—but its heavyweight status and population-dense environs hint that the outsized object may have eventually morphed into another, more familiar cosmic form. It may have become a giant elliptical galaxy, an egg-shaped collection of trillions of stars. When multiple large galactic mergers occur, this type of galaxy usually forms as a result.

“When we look at galaxies in a cluster of galaxies, they’re almost all elliptical, so they look old, and they look like fuzz balls of stars,” he says. “They don’t look like disks, but we don’t really know exactly what their history has been. So there could be [known galaxies] lurking there that are descendants of things like Big Wheel.”

“One of the really fun things about astronomy is that you often find things that you were not looking for, and they turn out to be sometimes even more interesting than what you were trying to do,” Steidel says. “It’s not a straight path all the time, and [Big Wheel] is what I would call a serendipitous discovery. Now that we know what to look for…, that, I think, will turn out to be quite interesting.”