If Life on Mars Ever Existed, This Bizarre Rock May Tell Us

The intriguing chemistry of a rock collected by the Perseverance rover could trace to microbial activity—or not

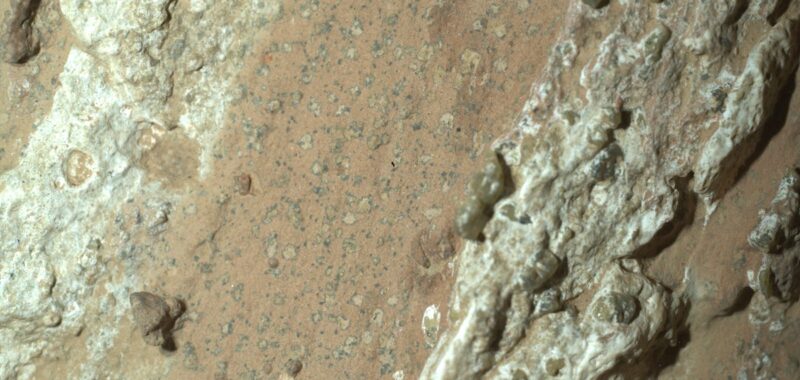

The black-ringed ‘leopard spots’ on a Martian rock might be evidence of chemical reactions that could have involved microorganisms.

NASA’s Perseverance rover has found possible hints of ancient life on Mars― one of the strongest signs yet of Martian life, according to planetary scientists. Dark-rimmed ‘leopard spots’ in a rock studied by the rover last year could be the remains of Martian microbial activity, researchers said at a conference today.

The announcement comes loaded with caveats. Yes, the spots look a lot like those produced by microbes on Earth. But the spots might have formed without the help of living organisms, researchers say, even if they don’t entirely understand the chemical and physical processes on Mars that would have been at work in that case.

For now, the discovery remains a 1 on the scale of 1 to 7 for evaluating claims of extraterrestrial life: 1 represents the detection of an intriguing signal, and 7 is a slam-dunk confirmation. Jim Green, the former chief scientist at NASA who developed the scale, says he would like researchers to make additional confirming measurements to move it up another notch on the scale. Doing that would require bringing the leopard-spot rock back to Earth for analysis. A sample is sitting in Perseverance’s belly, awaiting a ride off Mars for precisely that purpose.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Regardless of how things play out, the discovery is a significant entry in the history of searching for extraterrestrial life — and a test of researchers’ ability to evaluate potential biosignatures on other planets.

Lake-side real estate

Today’s talks, given at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas, were the first public presentation of a discovery that NASA teased in a July press release, which contained few scientific details. The agency’s caution comes from experience: decades ago, scientists claimed to have found signs of life in the Martian meteorite ALH84001, only for other researchers to find ways to explain the observations through geological, rather than biological, processes.

The data revealed today come from a rock in Jezero Crater, where the rover landed in 2021 to hunt for signs of Martian life. Aeons ago, the crater held a lake that could have been conducive to life. The rock formed in the channel of an ancient river that once flowed into the lake.

The rock contains dark peppery spots, which rover scientists nicknamed ‘poppy seeds’, and larger dark-rimmed blobs with lighter centres, dubbed ‘leopard spots’. Chemical analysis using the rovers’ instruments showed that the poppy seeds and the rims of the leopard spots are rich in iron and phosphorous. The centres of the leopard spots are rich in iron and sulphur, Joel Hurowitz, a geochemist at Stony Brook University in New York, told the conference.

These chemical enrichments suggest that the poppy seeds and leopard spots formed when carbon-containing ‘organic’ compounds in the rock reacted with iron and sulfate minerals. On Earth, such reactions are kicked off by microbes.

Although these reactions could have taken place without life if the rock were heated significantly, Hurowitz and his colleagues do not think that is probably what happened; the rock is fine-grained, which suggests that it has not been heated and recrystallized. If the rock’s temperature did remain low, modelling studies suggest that the spots could easily have formed if living things played a part in the process, Michael Tice, a geobiologist at Texas A&M University in College Station, said at the conference.

Settling the question

Still unknown is whether such reactions can occur without the presence of living organisms. “We should feel compelled to do a whole lot of laboratory, field and modelling studies to try to investigate features like this in more detail,” Hurowitz told the conference. “And ultimately bring these samples back home so that we can reach a conclusion with regard to whether or not they were or were not formed by life.”

NASA is facing enormous pressure to revamp its plans to bring as many as 30 of Perseverance’s samples to Earth. Early estimates that this mission would cost up to US$11 billion sent the agency back to the drawing board, but it has been unable to figure out a path forwards so far.

If scientists can get Perseverance’s samples into their labs, they could run sophisticated analyses, such as isotopic studies, that could help to reveal whether microbes were involved in forming the spots.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on March 12, 2025.