For most of the 20th century, each successive decade added about three extra years to people’s average lifespan in developed countries. For a person born at the turn of the 21st century, these incremental gains meant that they could, on average, live 30 years longer than someone born in 1900, allowing them to make it to their 80th birthday.

This phenomenon, referred to as radical life extension, was gifted to humanity by advances in various medical technologies and public health measures. Many scientists and lay people alike assumed that the trend would continue and that human lifespans would increase at the same clip indefinitely. Others, however, predicted that humans would hit a natural ceiling, with average lifespans of the world’s longest-lived countries plateauing well before 100.

New research on this hotly debated question now suggests that humanity has, in fact, reached an upper limit of longevity. Despite ongoing medical advances designed to extend life, the findings indicate that people in the most long-lived countries have experienced a deceleration in the rate of improvement of average life expectancy over the past three decades.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This is because aging—a series of poorly understood biological processes whose effects include frailty, dementia, heart disease and sensory impairments—has so far eluded efforts to slow it down, says S. Jay Olshansky, a professor of public health at the University of Illinois at Chicago and lead author of the new study, which was published in Nature Aging. “Our bodies don’t operate well when you push them beyond their warranty period.”

“As people live longer, it’s like playing a game of Whac-a-Mole,” he adds. “Each mole represents a different disease, and the longer people live, the more moles come up and the faster they come up.”

Olshansky became convinced of the immutability of the aging problem in 1990, when he published a paper in Science that predicted that our gains in life expectancy must slow down, even if advances in medicine accelerate. He concluded then that it was “highly unlikely” that humanity would exceed an average life expectancy of 85 years.

The paper met with widespread pushback, he says, because “there’s vested interest in this narrative of continued gains in life expectancy.”

Olshansky was convinced he was right, though. So he decided to “be a patient scientist,” he says, and retest his hypothesis once the real-world data came in. It took 34 years, but the wait has now paid off with “a definitive yes” in support of his original findings, he adds.

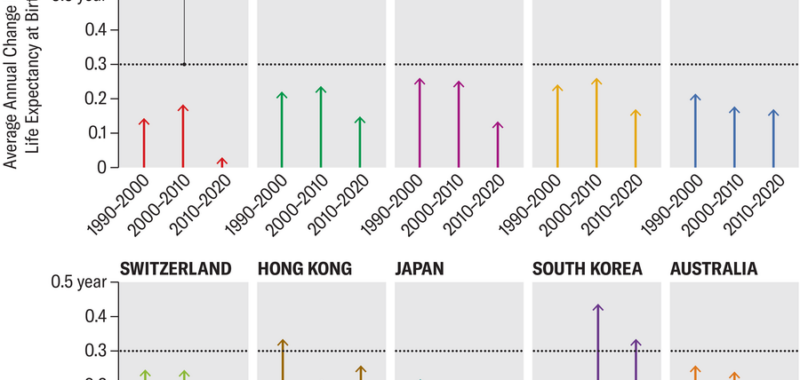

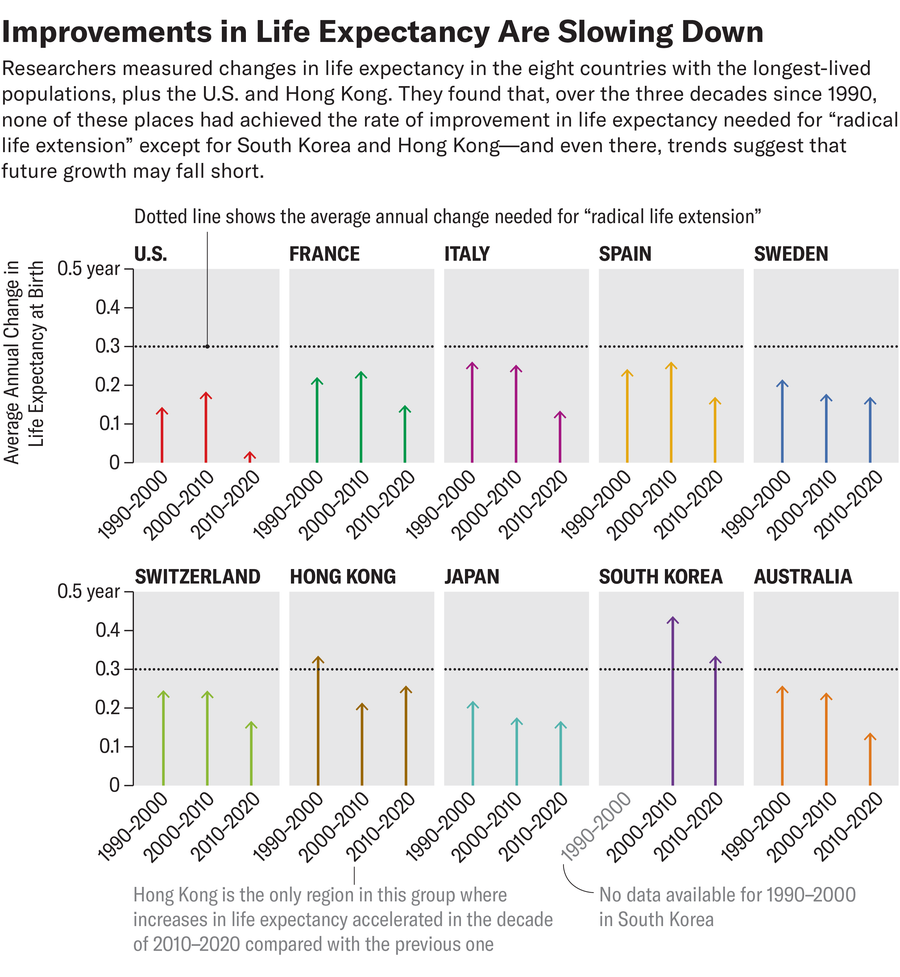

Olshansky and his colleagues took a straightforward approach: they examined observed changes in death rates and life expectancies from 1990 to 2019 in the world’s eight longest-lived countries—Japan, South Korea, Australia, France, Italy, Switzerland, Sweden and Spain—plus the U.S. and Hong Kong. They found that improvement in life expectancy decelerated in almost all of these places and that it actually declined in the U.S.

South Korea and Hong Kong were exceptions. They underwent recent accelerated improvements in survival, a phenomenon the researchers suspect has to do with the fact that both places concentrated their large increases in life expectancy only recently, in the past 25 years, Olshansky says. Even so, in Hong Kong—whose population is the world’s longest-lived—the researchers found that just 12.8 percent of female children and 4.4 percent of male children born in 2019 are expected to reach 100 years old.

The figures were significantly lower in the U.S., with only 3.1 percent of female children and 1.3 percent of male children expected to live to 100.

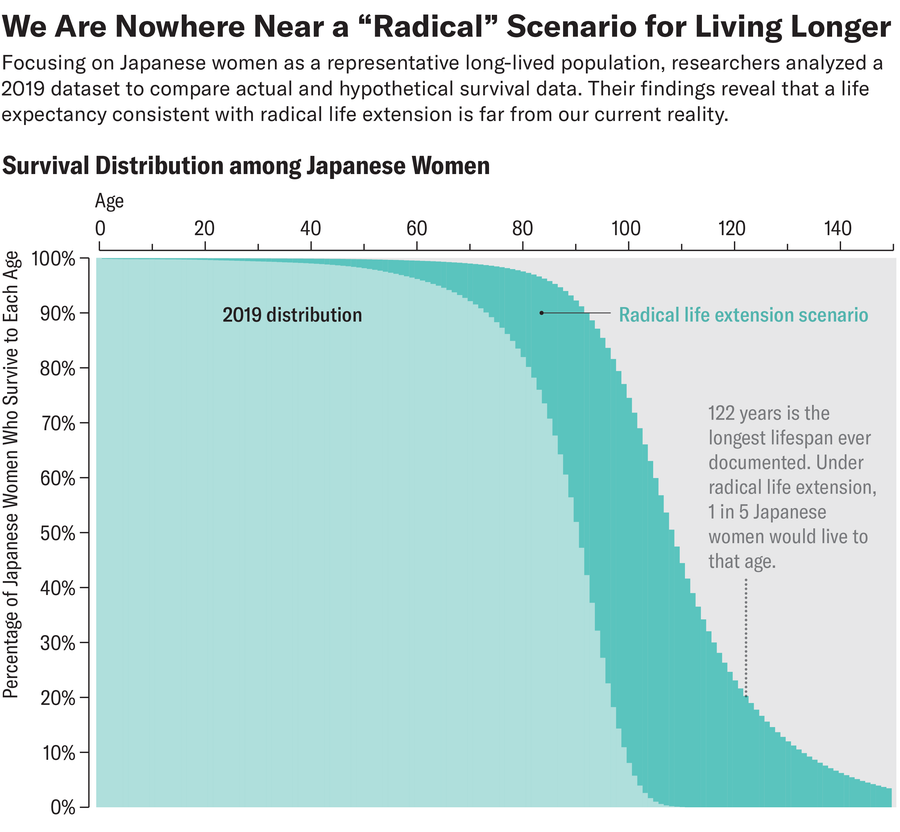

To put their findings into perspective, Olshansky and his colleagues also calculated what life expectancy would look like if humanity had actually kept pace with radical life extension. If that had happened, then 6 percent of Japanese women, for example, would be living to the age of 150, and around one in five Japanese women would be living past 120. “We didn’t call those scenarios ‘ridiculous’ in our paper, but we were hoping people would come to that conclusion on their own,” Olshansky says.

The new paper’s approach and conclusion “make perfect sense,” says Jan Vijg, a biologist and geneticist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who was not involved in the research. “There is really no evidence that survival to 100 will become a reality any time soon.”

The new paper’s findings mirror some prior research, Vijg adds, including a 2016 paper that he and his colleagues published that reached the same conclusion about lifespan limits. “After we published our paper, we got overwhelmed by an avalanche of responses, both scientifically and nonscientifically, that we were charlatans, that our data were flawed and that there was no evidence for a limit to life span,” Vijg says. “Needless to say, flaws in our data were never found.”

Despite the weight of the new evidence, Olshansky fully expects that he and his colleagues’ findings will be controversial.

He argues, though, that scientists should shift the focus away from the “untested hypothesis” of continued radical life extension and should instead pivot to geroscience—a relatively new field of research that is focused on extending people’s “health span,” the number of healthy years that they have to enjoy, but not their overall lifespan. Unless new technologies address aging itself, further radical life extension in already long-lived countries “remains implausible,” Olshansky and his colleagues wrote in their new paper.

Nalini Raghavachari, a program officer at the U.S. National Institute on Aging, who was not involved in the study, agrees that research should focus on understanding and achieving healthy aging. Clues for how to do that could come from some of the world’s longest-lived populations, she says. “A deeper understanding of the protective influences and mechanisms underlying exceptional health span could lead to the development of novel therapeutic targets and interventions to promote healthy aging,” Raghavachari adds.