Computers were ugly hulking gray or beige boxes then, taking up so much desk space. In 1996 I worked at Disney Interactive, my Windows 95 operating system skinned with an “X-Files” theme; when I arrived early, the TV show’s eerie chimes echoed across the empty office. Work was a lot like now, doing things using the computer and answering and sending emails. Important people flexed by doing none of that — they showed off by not having computers on their desks at all. At the end of the day, those of us with computers waited for them to shut down, slowly, before leaving. And then work was behind you.

Maybe you’d meet somebody out, remotely checking the answering machine plugged into your landline for messages. Maybe you’d go home to make dinner and catch the news on TV or NPR. Then, if you were into computers, you might turn on the one you had at home and dial in to the baby internet via modem and read funny things or post on message boards, waiting, always waiting, for the pages to load, line by line.

Did we have more time to read books then, or does it just seem that way? More time to consume news on a slower timetable, for sure. 1996 was an election year; Bill Clinton was running for his second term as president, and much of the conversation was dominated by political books. Colin Powell had fanned the flames about a possible run with his 1995 memoir, “My American Journey,” putting him on bestseller lists and the 1996 interview circuit. “There were some days I wished I had never started it,” he told C-SPAN, the universal writer’s lament. But he didn’t join the race.

That was just the preamble. The scores of others that followed included Newt Gingrich’s “To Renew America” and, from Republican nominee Bob Dole, “Unlimited Partners,” written with his wife, Elizabeth. “Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage” by Marshall Frady burnished the reputation of Jesse Jackson, a potential Democratic challenger who decided not to run.

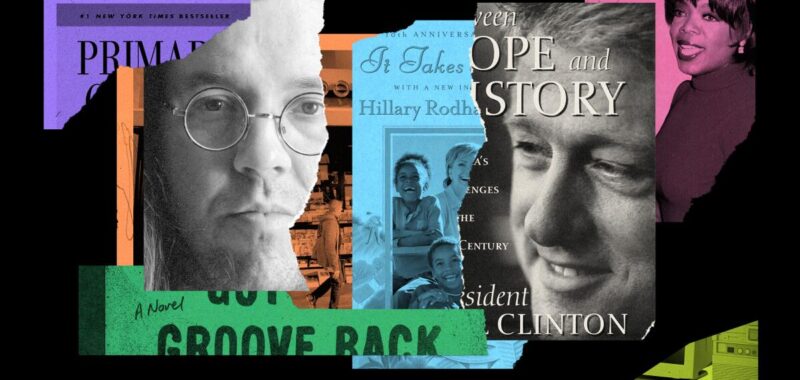

A popular incumbent, Clinton published a book to accompany his campaign, “Between Hope and History: Meeting America’s Challenges for the 21st Century.” He wasn’t the only one writing at the White House; Hillary Clinton released “It Takes a Village,” which topped bestseller lists.

The first couple also had bestselling detractors. “Blood Sport: The President and His Adversaries” by James B. Stewart was a salacious Whitewater exposé, while former FBI agent Gary Aldrich’s “Unlimited Access” was a vitriolic take on the Clintons’ failings in the White House.

But the biggest political book of them all was a novel. Technically. Roman-à-clef “Primary Colors” hit shelves in January, clearly based on Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. It was authored by “Anonymous” — and the question of who might have written it set off a feeding frenzy of speculation. The book topped bestseller lists and the Anonymous pursuit stayed in the headlines for months. People were obsessed. In February, New York Magazine published a cover story saying Newsweek columnist and CBS News contributor Joe Klein was the author, but he denied it so vehemently that speculation about others continued for months. In July, the Washington Post reported that, based on a handwriting analysis, it believed it was Klein after all. He called a press conference to admit it, facing down a crew of angry journalists. But his publisher was delighted, saying, “‘Primary Colors’ has become once again a media event.”

While all this political reading was in overdrive, people were still buying other books. The usual suspects (Michael Crichton, John le Carré and Tom Clancy) all published bestselling thrillers in 1996. Dean Koontz hit the bestseller list with “Ticktock,” a horror-comedy. That year, Danielle Steel published not one but two bestselling books. Terry McMillan scored a second bestseller with “How Stella Got Her Groove Back,” just as the film adaptation of her first, “Waiting to Exhale,” hit movie screens. Bestselling mysteries came from Scott Turow and Sue Grafton, whose “M Is for Malice” marked the midpoint of her alphabet series.

It’s remarkable that many of these authors are still writing, still hitting bestseller lists, 30 years later. Even those who have died are still publishing — Le Carré’s son Nick Harkaway, a novelist in his own right, continued his father’s George Smiley legacy with a new novel last year. Crichton, who died in 2008, has published four books posthumously, most often with credited co-authors. And although Clancy died in 2013, the Tom Clancy brand has continued, with his name prominently displayed on the book or two a year that have been published ever since.

One of the reasons these authors have such staying power may be the way the market was shaped in 1996. If you wanted to buy a book, it was easy to get to one of five huge national chain stores: B. Dalton, Barnes & Noble, Crown Books, Waldenbooks and Borders Books & Music. Their market dominance was so complete that publishing business watchers cautioned that they might have too much power. And if you were a real book lover in Los Angeles, you’d go to one of the independents — Vroman’s, Skylight (which opened that fall, after Chatterton’s closure in 1994) and Book Soup (albeit with different ownership) are still selling books today. 1996 bookstores that are no longer with us include Dutton’s, Eso Won, A Different Light, Sisterhood Bookstore, Brentano’s, Village Books, the Bohdi Tree and Midnight Special.

The extinction event looming on the horizon was Amazon, of course, which launched its website in 1995 and would grab the public’s attention in 1997 with its wildly successful initial public offering. In 1996, many retailers remained skeptical of online shopping and didn’t have full-fledged websites; customers were concerned about the security of online purchases. While that was soon to change, it meant that for books especially, 1996 was an eddy of calm before the meteor storm arrived.

And first, a dazzling ship arrived: Oprah’s Book Club. Announced in September, Oprah Winfrey had just two book-club sessions in 1996, but they were a genuine indicator of her power. After being selected by Oprah, Jacquelyn Mitchard’s “The Deep End of the Ocean” reached bestseller lists months after its debut. Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon,” published 19 years earlier, got a new paperback release that was an overnight bestseller. “I want to get the country reading,” the popular television host said, and she did. In later years, her choices would become instant bestsellers. Some literary types worried that TV and books were somehow at odds, that her tastes weren’t highbrow enough.

But readers who wanted highbrow had other places to turn. Wisława Szymborska, the Polish poet, won the 1996 Nobel Prize in literature “for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality.”

The Pulitzer Prize for poetry went to Jorie Graham for her collection “The Dream of the Unified Field.” The Times’ Jack Miles won the Pulitzer in biography for his weighty book “GOD: A Biography.”

On the fiction side, the winner of the Pulitzer was Richard Ford for “Independence Day.” The winner of the National Book Award was Andrea Barrett’s “Ship Fever and Other Stories,” beating out finalists “Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer” by Steven Millhauser, “Atticus” by Ron Hansen, “The Giant’s House” by Elizabeth McCracken and “The River Beyond the World” by Janet Peery.

Puzzlingly absent from those lists was what we can now see was one of the most important novels of 1996. “Infinite Jest” by David Foster Wallace is a work of generational genius. The novel is more than 1,000 pages long, funny and brilliant; despite its annoying fanboys, the book’s reputation gets ever brighter. “David Foster Wallace’s 1996 opus now looks like the central American novel of the past thirty years, a dense star for lesser work to orbit,” Chad Harbach wrote in n+1 in 2004.

Though some critics at the time were exasperated by having to read such a big, wordy book, The Times selected it as one of the best books of the year. Reviewer David Kipen celebrated Wallace’s “stupendously high-toned vocabulary and gleeful low-comedy diction, coupled with a sense of syntax so elongated that he can seem to go for days without surfacing.”

At the time, Wallace was living and teaching in Illinois, and instead of finding an agent in New York, he’d connected with Bonnie Nadell in Los Angeles. That westward shift was one of those quiet things that happened in 1996 whose repercussions would be felt in unexpected ways far into the future.

Like the first L.A. Times Festival of Books.