CLIMATEWIRE | NOAA has begun to limit the work it devotes to maintaining a pair of polar weather satellites — putting at risk the accuracy of both weather forecasts and extreme storm predictions, say former agency officials.

The move, outlined in a memo obtained exclusively by POLITICO’s E&E News, calls on the agency to take a “minimum mission operations approach” to the two probes. The satellites are part of the Joint Polar Satellite System, which serves as the backbone of three- and seven-day forecasts and early warnings for hurricanes and tornadoes.

The order means NOAA won’t do much to upkeep the satellites, which orbit the Earth’s poles 14 times a day. The March 28 memo calls for the deferral of discretionary activities including “modernization product maturation, flight software updates, decommissioning planning, ground system sustainment deployment(s), special calibrations, etc.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The reason for the move is because of anticipated “reduced flight engineering support,” according to the memo. The decision to defer the satellites’ maintenance comes as the Trump administration slashes NOAA’s contracts with outside vendors and looks to cut its workforce in half.

Former NOAA officials warn the move is a short-sighted decision with potential long-term consequences. Deferring software updates and other maintenance work may save some money right now, but the approach increases the risk of failure and could drive up costs in the long-term, said Rick Spinrad, who served as NOAA administrator in the Biden administration.

“As soon as you start having system glitches — and in the satellite world, system glitches are the name of the game — they’re going to fail to collect the data they need,” Spinrad said.

The stakes for failure are high.

JPSS “provides the majority of data that informs numerical weather forecasting in the U.S. and delivers critical observations during severe weather events like hurricanes and blizzards,” according to NOAA.

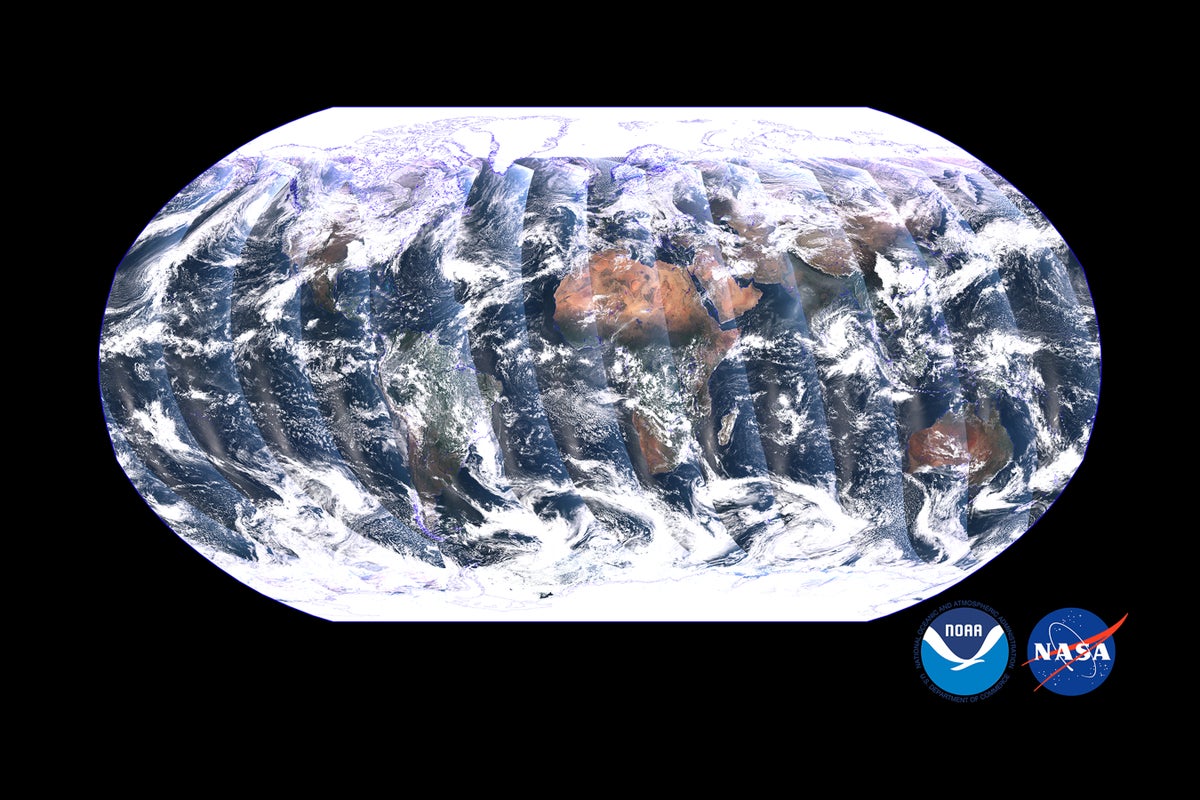

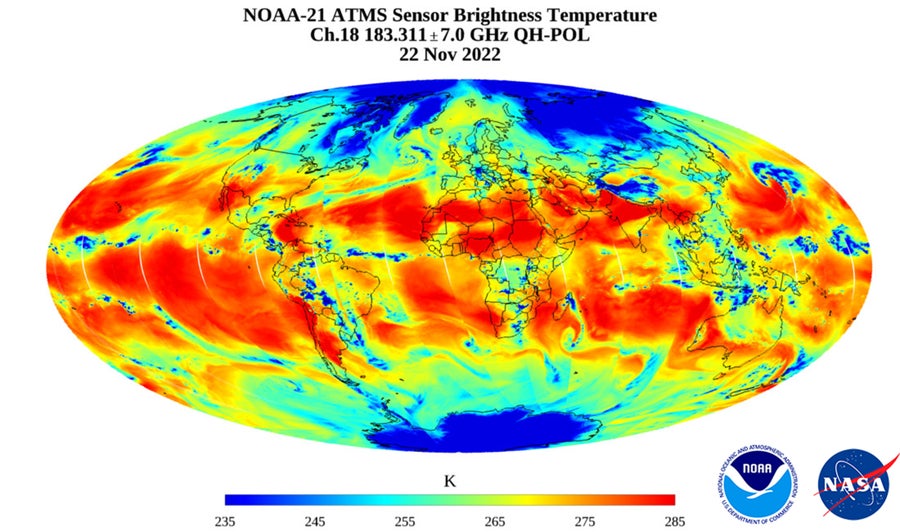

This image by the NOAA-21 satellite shows global water vapor.

Image processing by NOAA/Center for Satellite Applications and Research. Contributors: Mark Liu, Ninghai Sun, NOAA/NESDIS/STAR; Vince Leslie, MIT-LL, JPSS ATMS SDR Team

In a worst-case scenario, a failure could blind the country to a severe storm, potentially for days if the system has a significant issue, Spinrad said.

It’s unclear how much money the move will save. The section of the NOAA memo related to cost savings was left blank, and NOAA officials did not respond to a request for comment.

The total cost of the JPSS program was estimated at more than $13 billion, according to NOAA.

As it stands, the JPSS program is only partially complete. The oldest polar-orbiting satellite in the JPSS constellation is the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, which monitors long-term climate trends and biodiversity. That satellite was launched in 2011 and is nearing the end of its lifespan.

Two additional JPSS satellites are set to join the three in space right now, with the next one scheduled to launch no earlier than 2027. The federal government, during the Biden administration, signed a roughly $100 million contract for that launch with SpaceX, the rocket company run by billionaire Elon Musk, an ally of President Donald Trump.

Since Trump took office, Musk has led an aggressive campaign to slash both government spending and the size of the federal workforce, including at NOAA.

A fifth satellite is also in development and scheduled to launch in 2032. No one in the Trump administration has yet raised the possibility of canceling one or both future launches.

The new plan means NOAA and NASA will be less prepared to handle major issues that arise in the functioning of the satellites, according to Spinrad. Regular maintenance allows for problems to be addressed before they become serious. If something more serious were to occur, and the other satellites were also experiencing issues, the essential stream of weather monitoring data could be compromised for days, according to Spinrad.

Artist’s rendering of NOAA’s JPSS-2.

Spinrad likened it to driving around in a car that could be disabled at any point while placing confidence on a second backup car parked in a garage with a dead battery or oil leak that no one has checked in years. The likelihood of a series of cascading failures notably increases without regular maintenance, he said.

Data from the satellites — which are about as big as a pickup truck and powered by solar arrays — is shared with other governments, who pass along their data to the United States, Spinrad said. It’s part of a collaborative global system of weather monitoring.

For example, if a U.S. satellite collects data at one time of day, a European satellite might collect it later in the day. Collectively, they offer a comprehensive overview of global conditions that offer insights on incoming weather.

Losing a data stream — through the loss of a satellite, for instance — can erode the overall accuracy of this collaboration.

That’s a real risk, Spinrad said, because satellites need constant maintenance. Their orbits need to be monitored and occasionally repositioned, the sensors need to be checked to ensure they are working properly and data transmission has to be evaluated as well.

That long checklist is part of the reason former NOAA officials are arguing against the anti-upkeep order.

The cuts to the maintenance of the satellites is similar to last week’s proposed termination of a cloud usage contract for dozens of NOAA websites centered on climate change, extreme weather research and drought monitoring information. That termination would have destroyed a significant amount of research that would have been unrecoverable if the web pages were knocked offline. After news of the contract cuts became public, NOAA political appointees backed off the plan.

Andrew Rosenberg, who served as a senior official at NOAA during the Clinton administration, said the latest memo shows the NOAA cuts are being driven by officials who don’t understand the cost and consequence of what they are eliminating.

“Are you really saying that maintenance of high tech, extremely expensive equipment that provides vital information is waste, fraud or abuse?” he asked.

The move to defer the NOAA satellites’ upkeep is happening as three NASA satellites that provide essential climate and atmospheric data near the end of their life.

These probes could be offline within the year, and there are no plans to replace some of their specialized instruments, which provide information on long-term changes to the Earth’s ozone layer, planet-warming solar radiation and other key climate information.

One instrument for which there is no replacement plan is the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, which tracks forests, clouds, glaciers and oceans.

Scientists are hoping the NOAA satellites make up for that loss.

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2025. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.