A few days before Thanksgiving, President-Elect Donald Trump pledged to impose a 25 percent tariff on goods from Mexico unless the country halted the flow of migrants and drugs across the southern border. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum offered a stiff response, which was followed by what she called a “very kind” phone conversation between the two. Trump claimed that Sheinbaum had agreed to “close” the border, which she said was a misinterpretation. But she did say that there was “no potential tariff war.”

Meanwhile, Reuters reported that American growers have asked Trump to spare U.S. agriculture from mass deportations, lest labor shortages lead to a spike in grocery prices. Trump has not publicly responded.

Is there a deal in the making? History might offer insight into some of the options that Trump faces and what they portend.

In recent months, reporters have repeatedly asked me about Operation Wetback, the Eisenhower-era mass deportation of Mexican farmworkers that Trump has held up as a model for his plans to rid the country of unauthorized migrants. The deportation of a million farmworkers in 1954 was brutal and cruel. Truckloads of workers were dumped over the border in the northern Mexico desert, where some died from heatstroke. Others were sent across the Gulf of Mexico to Veracruz in cargo freighters that one West Virginia congressman called “hell-ships.”

Trump faces several options. One scenario has been sketched out by Stephen Miller and Project 2025: rounding up 10 million to 12 million unauthorized immigrants from workplaces, farms, and communities; detaining them in camps; and deporting them. Though this would be wildly expensive and logistically difficult, at least some are taking the prospect seriously. Stock prices in private prison companies rose the day after the election, and Texas officials announced that the state would provide land for the administration to erect detention camps.

A scaled-back version might involve flashy raids and the deportation of a million people or more. That would be bad enough, to be sure, and would have the additional effect of striking fear throughout all immigrant communities. There’d be serious harm, uprooting people from their homes and jobs and separating families, but it might play out like the wall that Trump promised in 2016 that he’d build on the border and force Mexico to cover the cost of. Once in office, he built a few hundred miles, called it beautiful, claimed victory, and everyone forgot about it. (Mexico, of course, didn’t pay a dime.)

The recent Trump-Sheinbaum exchange and the entreaties made by agricultural interests suggest a different possibility, that we might return to the sort of arrangement that prevailed in the 1950s, with all of its problems.

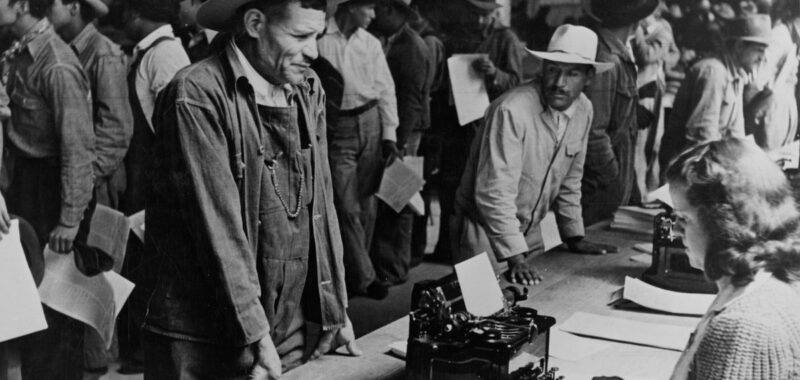

Although Eisenhower began by deporting more than a million Mexicans from the border area in 1954, apprehensions dropped to 240,000 the following year; 72,000 the next; and 44,000 the year after that. The vaunted “military operation” was a onetime spectacle, not an ongoing mass-deportation drive. Unauthorized border crossings dropped because the government opened up an alternative, allowing growers to hire laborers at the border. In other words, it turned erstwhile “illegal” workers into “legal” ones. Immigration officials called it “drying out the wetbacks.” The growers enrolled them in the so-called Bracero Program, the Mexican agricultural guest-worker program that had been in place since the early 1940s.

Under a bilateral agreement between the United States and Mexico, recruitment for the Bracero Program was supposed to take place at designated centers in various states in Mexico’s interior, making access to the program available throughout the country. By shifting hiring to the border, the government solved illegal immigration with a bureaucratic sleight of hand. After 1954, the number of bracero contracts increased. It grew by 25 percent in 1955 and then held steady at about 450,000 a year through the end of the decade.

A new guest-worker program like the Bracero Program might be legal—but its legality would be a sham.

The Bracero Program had begun in 1943 as an emergency measure to alleviate labor shortages caused by the draft during World War II. After the war ended, growers insisted that the program continue. They liked that it provided cheap labor under controlled conditions. Braceros worked on short-term contracts that required them to leave the U.S. upon their expiration. This was meant to ensure that there would be no families or communities established in the U.S.—and, of course, no future citizens.

Bracero farmworkers picked fruit in California, cotton in Arizona, sugar beets in Colorado, and vegetables in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. Employers routinely flouted regulations on wages, hours, and conditions because enforcement of such rules was scant. They housed workers in shabby barracks and shacks, gave them substandard food, and forbade them to leave the farms without a pass. Though “legal,” braceros were not safe from deportation either. Employers sent back to Mexico those workers who spoke out or organized to protect their rights. The immigration service also apprehended and deported braceros who “skipped” their contracts.

The guest workers, in effect, labored under a form of indentured servitude. The Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery after the Civil War, had also barred “involuntary servitude”—and the Foran Act in 1885 forbade hiring foreign workers under contract. In 1951, though, Congress lifted the ban to facilitate the Mexican labor program. Public Law 78 stipulated that Mexican guest workers would not displace or depress the wages of domestic workers and provided for decent conditions and protections from abuse. In general, however, these protections were not worth the paper they were written on. Most fundamental, braceros did not have the right to quit—the hallmark of free labor.

The Bracero Program wound down in the early 1960s, in part because the harvesting of some crops became mechanized. The program was also receiving public condemnation for its abuses and unfreedoms. Willard Wirtz, the secretary of labor under President John F. Kennedy, began aggressively enforcing the protections in the contracts. Growers gave up the program, and it ended in 1964.

Although the Bracero Program was the largest guest-worker program in U.S. history, involving 4.6 million contracts from 1947 to 1964, it was not the only such program, nor was it the last. In the 1960s, the U.S. imported 15,000 laborers from Jamaica to harvest sugar cane in Florida and pick fruit along the Atlantic seaboard. Congress created two new immigration categories for guest workers—H-2A in agriculture and H-1B in other industries—making the use of temporary foreign contract labor a permanent feature of the U.S. economic and immigration systems.

In 2023, more than 1 million people in the U.S. were on temporary work visas—310,000 in agriculture and 755,000 in other industries, such as high tech, theme parks, resorts, and universities. Like the braceros who came before them, they are bound to their employers and cannot strike. Many are deported if they complain about being cheated of their wages or if they are injured on the job. The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that the H2 “program is rife with labor and human rights violations … It harms the interests of U.S. workers, as well, by undercutting wages and working conditions for those who labor at the lowest rungs of the economic ladder.”

Guest workers have long been used around the world to address labor needs while keeping unwanted ethnic populations from becoming permanent residents or citizens of the host countries—among them, Turkish workers in Germany in the late 20th century and Bangladeshi and Filipino workers in the Gulf States today. Here in the U.S., “legalizing” illegal immigrants by making them guest workers would continue a dishonorable tradition. Americans should not be fooled if Trump announces it as a “beautiful” solution to illegal immigration.

The hidden lesson of Operation Wetback is that it’s actually easy to transform unauthorized immigrants into legally authorized workers. But if we want immigrants’ labor, we should not only allow them to come here legally, but also enable them to freely participate in the labor market and, if they wish, settle and become citizens. That would be true legalization.