WEST PALM BEACH — No one in the City Hall meeting room, surely, was under any illusions about their city’s segregated past, about the ways its historic Black neighborhoods had been forced for decades to subsist cut off and underserved.

But a presentation at a city commission meeting this week brought the hazy bigotries of decades past into vivid focus for the gathered leaders.

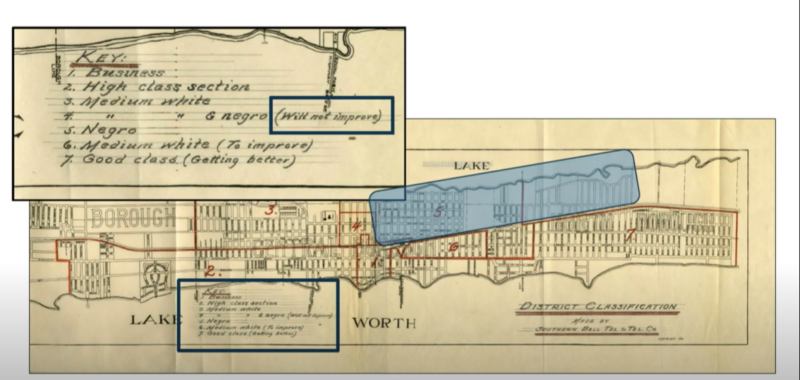

An overhead projector was displaying the yellowed paper of an old city document from 1923 on Monday, March 10. It was a West Palm Beach planning proposal, and it had a solution for what it called the “problem” of providing for the “negro population.”

“The question of providing for the future negro population of West Palm Beach is one of the important problems that needs to be solved,” the old master plan proposal stated.

West Palm Beach city planning proposals from 1923 reveal the city’s intention to segregate and underserve the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The documents were shown during a presentation by the Quantum Foundation at a March 10 city commission meeting.

It was a premise with a racist solution: ensuring that the city’s Black residents would confine themselves to certain sections of town — Pleasant City and the area around Tamarind Avenue, both north of downtown and west of Dixie Highway.

Such segregation would have to be done indirectly. The plan warned that “it is not possible legally to set aside such districts and restrict them to any race or color.”

But it continued: “…such districts can be established and every facility provided to encourage the settlement therein of people for which they have been planned.”

West Palm Beach city planning proposals from 1923 reveal the city’s intention to segregate and underserve the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The documents were shown during a presentation by the Quantum Foundation at a March 10 city commission meeting.

One benefit of pushing the Black population into that section of town, the plan noted, was that it would be partly separated from the rest of the city by existing railroad lines and future ones.

“The line of the railroad would thus definitely bound the district practically on all four sides,” it stated.

Mayor: ‘This is intentional, institutional’

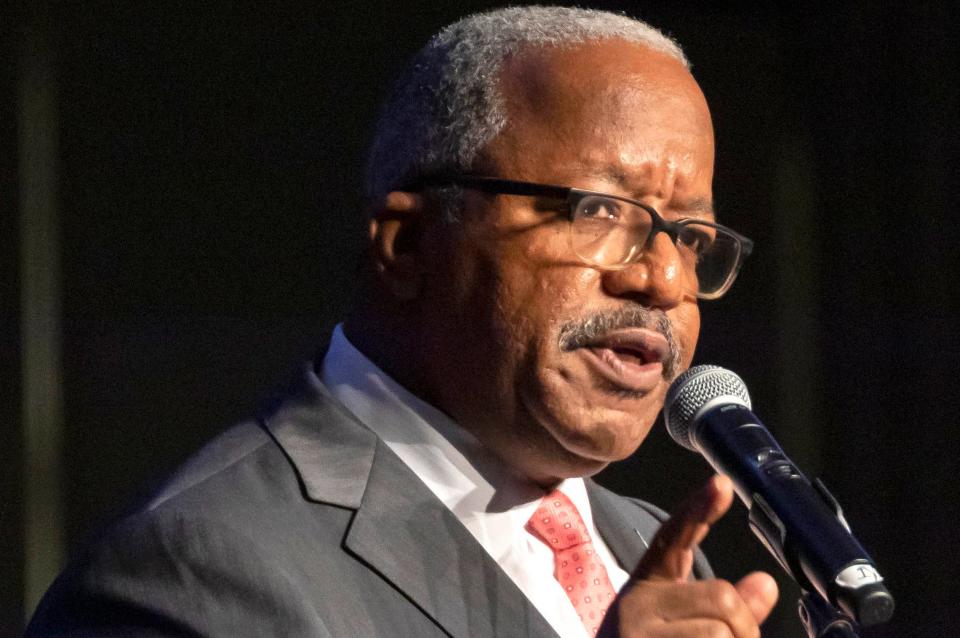

West Palm Beach Mayor Keith James, pictured in 2022.

It was a jarring presentation for Mayor Keith James and the city commissioners, offered up by an executive from the Quantum Foundation as historical context for new plans to revive the city’s Coleman Park neighborhood.

But it was hardly surprising.

A century later, the effects of segregation efforts remain. Those neighborhoods are still the traditional heart of the city’s Black community, and they remain largely cut off by the same railroad tracks and underdeveloped compared to the fast-growing neighborhoods to the east.

West Palm Beach city planning proposals from 1923 reveal the city’s intention to segregate and underserve the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The documents were shown during a presentation by the Quantum Foundation at a March 10 city commission meeting.

“Let this sink in, everyone,” James, the first Black mayor since the city moved to a strong-mayor system in 1991, told meeting attendees after the documents had been displayed.

“This was part of the city’s master plan back in 1920,” he said. “I don’t want us to rush through this. This is intentional, institutional. So when people talk about the lack of progress in some of these communities, that was designed.”

Indeed, there was more to the historic presentation. A slide showing yellowed city maps revealed the lack of paved streets and sewer systems in what had been designated the “negro” neighborhood. A notation next to it made clear the city’s intentions: “Will not improve.”

West Palm Beach city planning proposals from 1923 reveal the city’s intention to segregate and underserve the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The documents were shown during a presentation by the Quantum Foundation at a March 10 city commission meeting.

Raphael Clemente, executive director of a Quantum Foundation initiative called Palm Beach Venture Philanthropy, was leading the presentation, and he called attention to the notation.

It meant, he said, that “the city will not make investments for infrastructure improvements in these neighborhoods.”

West Palm Beach city planning proposals from 1923 reveal the city’s intention to segregate and underserve the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The documents were shown during a presentation by the Quantum Foundation at a March 10 city commission meeting.

“For the vast majority of that area, particularly north of Banyan (Boulevard), there was no street pavement, there was no water system and there was no sewer system,” he said, “even though these were neighborhoods that were occupied, and quite densely occupied.”

Six years after the planning proposal was submitted, city leaders in 1929 approved an ordinance to officially designate Pleasant City and adjoining neighborhoods as the “negro district,” according to a city timeline.

West Palm Beach city planning proposals from 1923 reveal the city’s intention to segregate and underserve the city’s historic Black neighborhoods. The documents were shown during a presentation by the Quantum Foundation at a March 10 city commission meeting.

What are the plans for Coleman Park? ‘An opportunity for meaningful change’

Clemente, who led the city’s Downtown Development Authority for 12 years before moving to the Quantum Foundation, had a particular point in showing the century-old documents, which he said an acquaintance had unearthed in an historic archive.

Clemente and the foundation are putting together a plan to reinvigorate the Coleman Park neighborhood, which sits squarely in the city’s historic Black sector, north of Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard and east of the Florida East Coast Railway tracks.

The plans are ambitious, from murals and public art to attracting a fresh food market. The foundation wants to ensure all bus stops in the neighborhood have benches and shade, start a tree-planting initiative and add buffering along the Brightline railyard.

An oversized baseball at the Coleman Park Community Center in West Palm Beach’s Coleman Park neighborhood attests to its gloried past in this file photo. The center is built in the old Lincoln Park, where Negro League legends such as Satchel Paige played.

It wants the city to extend 17th Street to create a better connection between Douglass Avenue and Tamarind. It envisions a community land bank and a business incubation program supporting the neighborhood.

Achieving all those things will require investment from the city government, he said, but it was needed to make up for decades of underinvestment and discrimination.

“What took 60 or 70 years to do I think we can significantly undo in a decade,” he said. “This is an opportunity for meaningful change.”

Commissioner Shalonda Warren, who is Black, said it was “very stunning” to see the old city plans — not just for the chilling formality of their segregationist aims, but the way the effects still overshadow the city.

“My heart is pounding in my chest now today,” she said, “just in retrospect of how deliberate the exclusion was and how there’s still barriers that are being overcome today more than a century later.”

James said residents in those neighborhoods today have every reason to distrust the city.

Two children cross the Florida East Coast Railway tracks near 23rd Street as they head to Pleasant City Elementary School in 2004. According to 1923 West Palm Beach documents, the city purposely tried to confine Black residents to certain sections of town — Pleasant City and the area around Tamarind Avenue. One benefit of pushing the Black population into that section of town, the documents noted, was that it would be partly separated from the rest of the city by existing railroad lines and future ones.

“This is a city that basically screwed them, for lack of a better word, for years,” he said. “So why should they trust city government? So that’s a hurdle that we have to overcome as city leaders, unfortunately, but it’s understandable.”

James noted with dismay that one of the authors of the proposed city plan had studied at Harvard University, where James received his bachelor’s and law degrees.

“What he probably never anticipated,” he said, “was that a ‘Negro’ would be mayor of this city.”

Andrew Marra is a reporter at The Palm Beach Post. Reach him at amarra@pbpost.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Old plans for segregated city remind West Palm leaders of racist past