An excerpt from From Error to Ethics: Five Essential Lessons from Teaching Clinicians in Trouble.

Clinicians must be scrupulously honest in and out of work

About 70 percent of the clinicians who attended the course had been accused of dishonest conduct. It is so common that the ‘dishonesty’ file on my computer contains eight sub-sections:

- Cheating in exams

- Defrauding the National Health Service

- Dishonesty in job applications

- Dishonesty in a non-medical context

- Failure to disclose criminal offence to the regulator

- Falsification of medical records

- Falsification of other documents

- Other types of dishonesty

Clinicians who have engaged in dishonesty are in a challenging position because dishonesty is difficult to cure. If a clinician has failed to insert a central line safely, for example, he or she can attend a course to master this skill, but what about the clinician whose failure is an act of dishonesty? There is a presumption that dishonest clinicians suffer from a character flaw that renders them untrustworthy and potentially unsuitable for practice, but that is not necessarily the case.

The philosopher Judith André has divided ethical behavior into three stages: 1. moral perception (awareness that ethics is in play), 2. moral reasoning (working out, through reasoning, the morally right action), and 3. moral action (acting on the conclusion of your moral reasoning).

Although ethical issues do not come pre-labelled (hence the frequent failures of moral perception), most of the attendees knew that they had acted dishonestly and hence in breach of an ethical rule. They usually faltered at the next stage: Moral reasoning. In weighing up the pros and cons, they failed to ascribe sufficient weight to the wrongness of their deception, in particular the potential damage to trust. They convinced themselves that their dishonesty, while technically a ‘rule breach,’ was harmless and therefore justified, especially if no patients were directly affected.

The clinician who used a smartphone to check answers in a professional exam believed it was wrong but harmless. So too the doctor who made up internships to boost a CV, the doctor who falsely added FRCP (Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians) to his name, the doctor who left his NHS duties early to do private work, or the dentist who claimed NHS compensation for fictitious procedures. The dentist was investigated by the NHS Counter Fraud Authority, convicted of fraud by false representation, and narrowly avoided a custodial sentence in the Crown Court.

Only in hindsight did the clinicians realize that their actions were an abuse of trust, with potentially adverse consequences for current patients or, at least, future patients. I ask them, “Who is less likely to trust you and your profession because of your actions, and why?” and this prompts them to think about their patients, colleagues, regulators, the public, and any other parties whose trust they may have damaged.

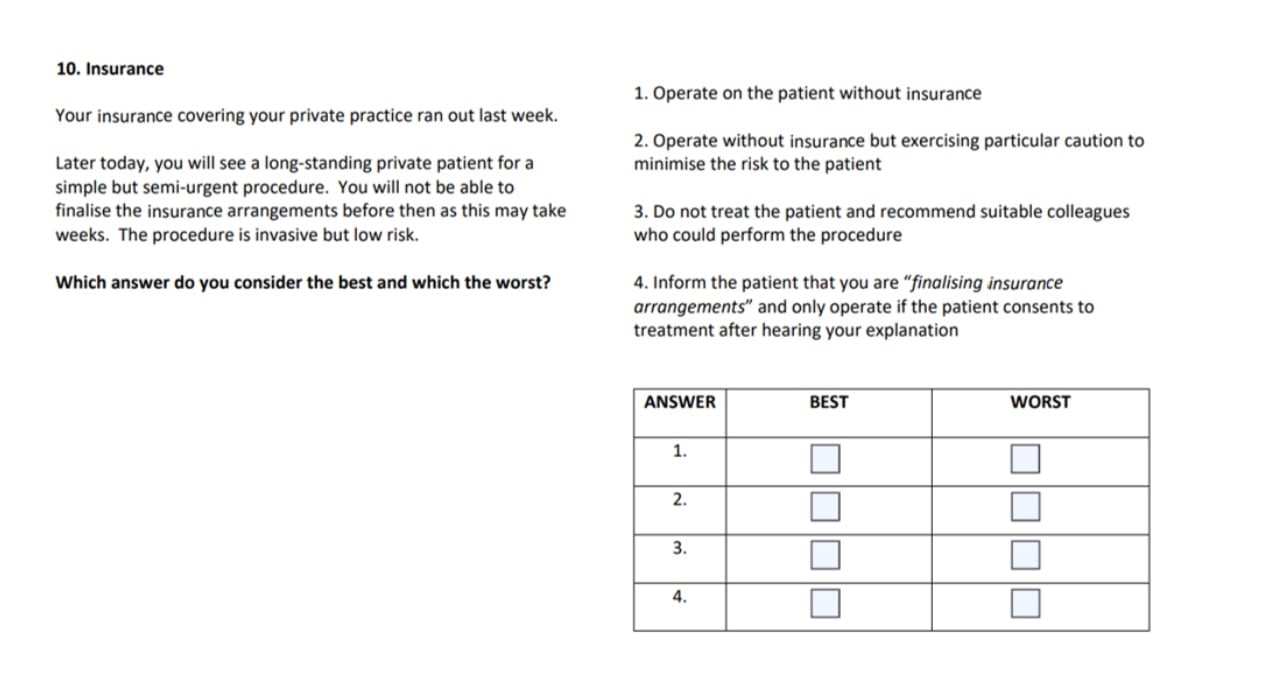

The issue of dishonesty looms so large in my caseload that, with the assistance of a psychologist and six medically qualified professors of medical ethics, I developed an honesty test. The test consists of 22 real-life scenarios, each with four possible answers. In each case, respondents are asked to select the best answer and the worst one. Below is an example, which you are invited to attempt.

Option 1 is dishonest (and, in some jurisdictions, unlawful) as patients reasonably assume that their treating clinician is insured. It would be tragic if, in the event of negligence leading to serious harm, the patient was deprived of compensation because the clinician was uninsured or inadequately covered. In the UK, the General Medical Council expressly states in Rule 101 of Good Medical Practice: “You must make sure that you have appropriate and adequate insurance or indemnity that covers the full scope of your practice. You should keep your level of cover under regular review.”[/caption]

Option 1 is dishonest (and, in some jurisdictions, unlawful) as patients reasonably assume that their treating clinician is insured. It would be tragic if, in the event of negligence leading to serious harm, the patient was deprived of compensation because the clinician was uninsured or inadequately covered. In the UK, the General Medical Council expressly states in Rule 101 of Good Medical Practice: “You must make sure that you have appropriate and adequate insurance or indemnity that covers the full scope of your practice. You should keep your level of cover under regular review.”[/caption]

Option 1 is the worst as it shows no appreciation of the risks of operating on a patient without insurance.

Option 2 remains dishonest, however cautious the clinician. In real life, this was the option selected by the doctor, who had declined to renew his insurance as he considered it too expensive.

Option 3 is the best. It is an honest and prudent response.

Option 4 provides an unclear explanation of the insurance situation and may leave the patient believing that insurance is in place.

I administer the test to the clinicians as an ethical training tool. Although a strong performance in the test does not guarantee honest conduct in practice, it at least shows a capacity to distinguish right from wrong in the domain of truth-telling.

The take-away message is that clinicians must act honestly in and out of work, whether it is to patients, colleagues, employers, insurers, or anyone else, and they must understand why this duty is so revered by their regulator.

The simple answer to the “why” question is that dishonesty tends to erode trust, not only in the clinician but in the medical profession as a whole. If Howard Brody believes medical ethics is about the responsible use of power, the bioethicist Rosamond Rhodes contends that the core duty of medical ethics, from which all other duties are derived, is to seek trust and be deserving of that trust. Regardless of whose theory is preferred, power and trust are central themes of the course.

Daniel Sokol is a medical ethicist and author of From Error to Ethics: Five Essential Lessons from Teaching Clinicians in Trouble.