Today, in the mail, I received a claim summary for medical care that my wife received. She saw an orthopedic PA for an achy knee and got a shot of a slippery substance that was supposed to be superior to steroids. “Is this stuff expensive?” she asked him. “Don’t worry about it,” he said. “You have Medicare. It will cover it.”

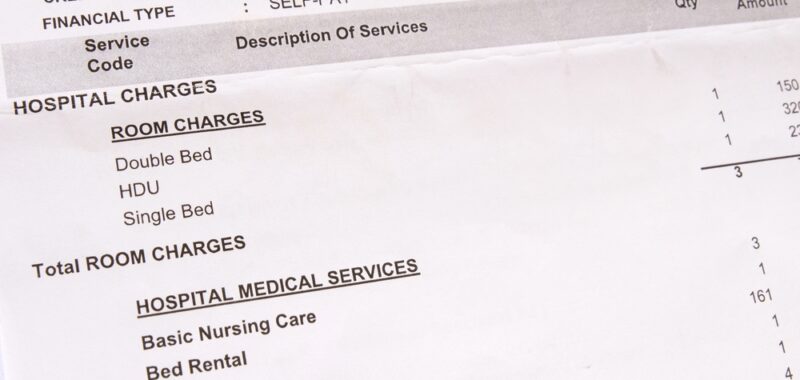

It didn’t help her knee, though, and she moved on to NSAIDs and forgot about the visit until her EOBs (Explanation of Benefits) arrived. “Hey, you’ve got to see this,” I said. “Your insurance was billed $22,655, and I’m not sure what it was for.” Neither was she. There was nothing on the claim summary that specified the procedure, the provider, or the billing codes. The Reason Code said only Surgery-Bone/Muscle, Office Visit, and Drugs with a date of service. “What did you have done on April 4th this year at the hospital?” “I don’t remember,” she said, and neither did I. So we looked at the calendar for that date, which is how we remind ourselves about the recent past, and saw it said, “Ortho, 9 am.” “Do you mean they billed all that money just for THAT?” she asked incredulously. Now I had a decision to make: whether to try and explain to her how the RBRVS (Resource-Based Relative Value Scale) worked or just tell her they only got $2,600 from Medicare and her secondary, and she didn’t owe them anything. I made the wrong choice.

“It doesn’t matter what your provider charges,” I began. “There is an assessed value for every procedure. The hospital billed $11,290 for the injection, but your insurance only paid a small portion of it. You saved $8,841.81! You saved $133.81 on the visit, and they didn’t pay anything on the $10,960 drug charge, which they bundled with the procedure. You owe nothing.” That didn’t seem to assuage her, though. “My parents bought their house for less than half of that,” she said. (She always likes to compare today’s prices to what her parents spent in 1950 for their home in Whittier.) “And nothing on this tells me who did what, and no one told me what it would cost,” she complained. “Why does it cost so much? I was only in there for half an hour and never saw a doctor.”

I had no good answers except to say that providers like to charge in excess of what their highest-paying insurance companies might allow, knowing they’re not going to get it but that they’re not going to miss out on any reimbursement increases either. “And what about providers that don’t accept Medicare assignment and patients without any health insurance at all?” she asked. “Do they have to pay the full amount? No wonder medical bills are the largest cause of bankruptcy in this country, and people lose their homes and are tossed out onto the street.” I could see that she was really upset but confessed I didn’t know what she could do about it. “Maybe you should complain to the hospital,” I suggested, trying to be helpful.

So she did. First, she called the hospital’s billing office and was told her charges didn’t come from them but from her provider’s office. A call there had her on hold for a while until she was asked to leave a message and a callback number. Nobody called back, so she tried again with the same result. Finally, someone from their central billing office did call but could only tell her, “That’s just the cost,” with no explanation. She was given the number of the patient advocate, who also wasn’t there, necessitating another left message. A callback to the ortho office was returned by a helpful person who said she would look into it. By the end of the day, her EOB was a jumble of scrawled names and phone numbers, and she had no idea what codes were used or who made the charges.

Her friend Sal pointed out that there was a number to report fraud on the EOB. She hadn’t actually had surgery, Sal said, just a needle poke. I said I thought that might be considered a surgical procedure. Again, trying to be helpful, I said, “If I had the codes, I would look them up. If I knew who made the charges, I would call them up.” Neither being the case, I’d run out of ideas and motivation.

Since I am the person who gets the daily mail at our rural delivery box, I vowed to stop showing my wife any more of her EOBs, lest this futile cycle repeats itself and she wastes another day on the phone. Seeking an explanation for medical charges is like falling into a black hole, I thought. Looked at another way, I could, if I chose to, think that Medicare and her secondary just saved me $22,655! That’s putting a positive spin on it! When you get lemons, it’s best to make lemonade.

Sandy Brown is a family physician.